Ambrogio de Predis

Bianca Maria Sforza, probably 1493

Oil on panel, 51 x 32.5 cm (20 1/16 x 12 13/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Widener Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

“There is nothing in our civil life that is more difficult than properly marrying off one’s daughters.”

—Francesco Guicciardini2

Renaissance marriages were not simply personal matters; they were crucial to the network of alliances that underlay a family’s prosperity and prospects and that, in turn, formed the fabric of loyalties, affection, and obligation that supported civic institutions. Arranging a suitable match involved family, friends, associates, and political allies. In aristocratic families, marriages were a currency of dynastic and diplomatic exchange (as in the case of Bianca Maria Sforza)—and they were not much different among the merchant families of republican cities. In Florence, for example, Lorenzo de’ Medici, de facto leader of the ostensibly-republican state, considered negotiating marriages among supporters a worthwhile use of his

Florentine 15th or 16th century, probably after a model by Andrea del Verrocchio and Orsino Benintendi

Lorenzo de’ Medici, 1478/1521

Painted terra-cotta, 65.8 x 59.1 x 32.7 cm (25 7/8 x 23 1/4 x 12 7/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

time and energy. Marriage not only reflected order, it was a civilizing influence on which the whole of society depended.

Brides, especially in Florence, were typically much younger than grooms. Women as young as fourteen were often married to men in their thirties, partly to ensure the bride’s virginity. The age disparity had a number of consequences. Young men were more or less free to visit prostitutes, who were semi-sanctioned in certain outlying districts. Relations between male youths and older men were regarded as fairly routine, particularly in humanist circles, in which ancient Greece provided a respected model. And, of course, the large number of very young brides corresponded to a large number of widows. Children of men who died remained in the man’s home and a part of his extended family; his wife did not. Instead, widows returned to the control of their own families, who now had to reassume their support or scramble to arrange a second dowry sufficient to attract another marriage proposal.

Weddings and Dowries

Marriage customs varied somewhat from one city to another; this account is based primarily on the many descriptions of weddings that survive from Florence, but it reflects general practices elsewhere in Italy. Before 1563, when reforms enacted by the Council of Trent systematized and formalized the process, the only requirement for marriage was the mutual consent of a man and woman not already married to someone else. Priests, ceremonies, and even witnesses were unnecessary. That did not mean, however, that weddings lacked elaborate ritual. Nor did it imply that couples chose their partners themselves.

A likely match was identified many years before a wedding, perhaps suggested by a broker or influential family connection. Negotiations between two families were sometimes sealed until the bride reached puberty and a suitable dowry could be amassed. Dowries, which consisted of goods such as clothing and jewelry as well as money or property, were among the greatest financial obligations that families with female children faced. Parents hoping to elevate their status paid large sums to place their daughters in advantageous unions, but even marriages among social equals required substantial investment. In Florence, a special public fund supported by an annual tax provided dowries for orphaned girls. Wealthy individuals also gave dowries for poor girls as acts of pious charity.

Grooms, too, were expected to provide gifts; among the wealthy, these often included gems and luxurious clothes for the bride to wear during the wedding festivities (see “Wedding preparations for Caterina Strozzi”). Gifts, which served as much to advertise the groom’s status as to please his new wife (and her family), remained his property. Some husbands later sold their wives’ wedding dresses; elaborate and colorful clothing would have become unsuitable after a few years of marriage, at which point women were expected to adopt more sober dress.

As the date of his wedding approached, a Florentine groom dined at the bride’s home and presented gifts. His visit was followed by a larger gathering of relatives from both families—males only—during which the final terms of the match were hammered out: the size of the dowry, a schedule for its payment, and the date of the nuptials. The arrangements were made public, giving outside parties a chance to raise objections. At this juncture, the bride herself was finally, albeit briefly, involved. During the ring ceremony (anellamento), which took place at her home, male and female relatives from both families looked on as she received a ring from her husband to be. A celebration followed, with more gifts and a festive meal.

Legitimization of the couple’s union (nozze) followed a procession through the streets of the town, as the bride—together with the groom’s gifts to her and her dowry goods—was moved from her childhood home to her husband’s house. In Rome, but not in Florence, the bridal couple normally stopped in church to attend a mass along the way. Roman brides proceeded astride a white horse, wearing belts their fathers had put around their waists to emphasize their chastity.

Marco del Buono Giamberti and Apollonio di Giovanni di Tomaso

The Story of Esther, 1460–70

Tempera and gold on wood, 44.5 x 140.7 cm (17 1/2 x 55 3/8 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

The wedding depicted on this panel, which was once part of a wedding chest, is that of the biblical Esther, but the action has been translated in time and place to fifteenth-century Florence.

These elaborate and very public festivities helped defuse any lingering dissatisfaction on the part of the two families whose interests were now joined (disputes over dowry amounts, for example) or any others who might have felt unfairly treated during marriage negotiations. Such resentment must have been somewhat common, given that a statute enacted in Florence prohibited onlookers from throwing stones or garbage at a wedding procession.

Public display encouraged lavish spending and at various times it prompted sumptuary laws designed to hold such spending in check. It also helped create a vogue for specially prepared marriage chests. Usually called cassoni today (but known as forzieri in Renaissance Florence), the chests were used to transport the wedding goods—dowry and groom gifts—during the wedding procession and to store them once the bride and groom had settled into their new home.

Weddings and the arrival of brides naturally occasioned redecorating at the groom’s home, often including installation of spalliere with narrative scenes. Long and horizontal, like cassone panels but a bit larger, spalliere were set over chests, beds, or other furnishings, appearing something like backrests. Eventually they were incorporated into the wainscoting. Some may have been set higher on the wall than the word “spalliera” (from “shoulder”) suggests. Probably one reason they grew more popular than the painted cassoni was that the wall-mounted panels could be seen more easily. A painter’s skill in using perspective, for example, would be hard to appreciate in a scene set almost at floor level.

Cassoni and Spalliere

Marco del Buono Giamberti and Apollonio di Giovanni di Tomaso

Cassone with The Conquest of Trebizond, 1460s

Tempera, gold, and silver on wood, distemper on inner lid, 100.3 x 195.6 x 83.5 cm (39 1/2 x 77 x 32 7/8 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

Between the 1370s and about 1470, most cassoni had painted decoration. The outsides often featured heraldic devices and narrative scenes, while the interior of the lid—seen only in the privacy of the home—frequently showed reclining nudes or cavorting putti, or textile-like patterns that mimicked the actual fabrics stored inside. Few cassoni survive intact; their various panels have been separated and are almost always displayed as individual easel paintings now. After about 1470, most cassoni were decorated with heavy wood carving or intarsia instead of painted scenes. The subjects once painted on the chests moved to the walls.

Florentine, first half of 16th century

Cassone made for Strozzi family

Walnut and poplar, 191.5 x 64.2 x 69.7 cm (75 3/8 x 25 1/4 x 27 7/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Widener Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

The Trebizond cassone

The Trebizond cassone was long thought to have been a rare intact survivor, but conservation work has revealed that it was reconstructed and is not in its original state; still, it gives an indication of how the chest would have looked during the sixteenth century.

The carved cassone is decorated with the crests and emblems of one of Florence’s most prominent families. Such carving was often highlighted with gilding.

Both cassoni and spalliere offered spaces for families and artists to explore themes related to love and marriage. Most common were scenes of conquests and triumphs, episodes with suitable moral messages about the duties of husbands and wives from myth and the Bible, or imagery taken from Ovid, Petrarch, Boccaccio, and other ancient or Renaissance authors. The values celebrated in these paintings—in the decoration of almost all objects made for weddings and newly formed households—were those most desired in the bride herself: beauty, virtue, purity, duty, and fertility.

Although a husband and wife would have had little opportunity to know each other before their wedding, most marriages seem to have developed into companionable, if not loving, relationships. Wives had few individual rights, but many exercised considerable power within the family and household. Business took many husbands away for extended periods, necessitating that their spouses play an active role in family affairs.

Leon Battista Alberti

Leon Battista Alberti, a humanist and architect who also wrote a manual on family life, signaled that wedding chests were not to be counted as ordinary storage. He teased wives about their appropriate use:

Dear wife, if you put into your marriage chest not only your silken gowns and gold and valuable jewelry, but also the flax to be spun and the little pot of oil, too, and finally the chick, and then locked the whole thing securely with your key, tell me, would you think that you had taken good care of everything because everything was locked up?3

A Husband’s Absence

Bernardino Licinio

Portrait of a Woman Holding her Husband’s Portrait, c. 1530s

Oil on canvas, 77.5 x 91.5 cm (30 1/2 x 36 in.)

Castello Sforzesco, Milan

Alinari/Art Resource, NY

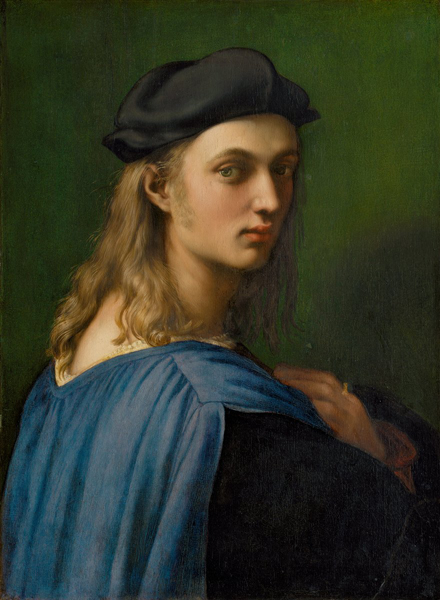

Raphael

Bindo Altoviti, c. 1515

Oil on panel, 59.7 x 43.8 cm (23 1/2 x 17 1/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

A husband’s absence could give new importance to his portrait. The identity of the woman who holds her husband’s likeness in Licinio’s picture is unknown, and her wan expression is a bit wistful and remote. The other picture is quite different. Raphael painted his friend, wealthy Florentine banker Bindo Altoviti, in an almost theatrical pose. He turns to fix the eye of the viewer, and Bindo perhaps intended his portrait to connect with one viewer in particular: his wife, Fiammetta Soderini. Bindo’s flushed cheeks contribute to the impression of passion, and a ring is prominent on the hand he holds above his heart. Bindo and Fiammetta, the daughter of a prominent Florentine family, were married in 1511, when Bindo would have been about twenty years old. The couple went on to have six children, but Fiammetta continued to live in Florence while Bindo’s business with the papal court required his presence in Rome. This portrait, which apparently hung in the couple’s home in Florence, would have provided Fiammetta with a vivid reminder of her absent husband. It remained in the Altoviti family for nearly three hundred years.