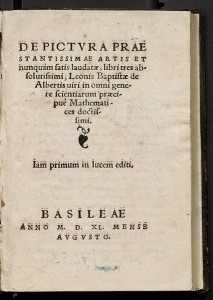

Title page from Leon Battista Alberti, De Pictura (On Painting)

Published Basel, 1540

Library, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, David K. E. Bruce Fund

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

Cennino Cennini wrote a handbook for artists around 1390. The first such book produced in Italian, it is primarily a compendium of practical advice—full of recipes for colors, glues, and sizes; methods for making the best charcoal; and techniques for applying gesso and gilding. It has provided a wealth of information about how early Renaissance art was made and is an important tool today for painting conservators. In his opening chapters (see “Excerpts from Cennino Cennini’s Handbook”), Cennini notes that the arts require a combination of arte (technical skill) and fantasia (imagination). Here is a foretaste of things to come. In the next century Leon Battista Alberti, Leonardo da Vinci, and others wrote treatises for artists that dealt less with the materials and techniques that most occupied Ceninni and instead concentrated on how the artist should prepare mentally. Thus, Alberti gave systematic form to one-point perspective, and Leonardo turned his scientist/naturalist eye to the operation of light and colors. Both imputed to the artist skills of the mind, equal to or greater than those of the hand. Art, they argued, ought to have a place among literature, philosophy, and natural history. The Renaissance saw the transformation of the medieval artisan into someone closer, though not identical, to the modern conception of the artist. This essay examines artistic training and practices, workshops, guilds, and academies—and the creation not simply of a new profession but of a new way of looking at art and artists.

In late fifteenth-century Florence, wood-carvers were more plentiful than butchers: art, even more than meat, was considered a necessity of life. That that was true among the wealthy may not come as a surprise (they could afford both), but the market for art was also driven by corporate and civic patrons and people of modest incomes. In 1472 the city boasted fifty-four workshops for marble and stone, forty-four master gold- and silversmiths, and at least thirty master painters—in a population of about forty thousand residents. Of the painters, we probably know the names or work of only a third (or less) of all those who were active.

Florence, however, was not entirely typical; the density of artists was not equal across Renaissance Italy. One modern scholar’s survey of six hundred “creative elites” (which included poets and humanists as well as visual artists and architects) found that only two regions, Tuscany with 26 percent and the Veneto with 23 percent, together accounted for nearly half of the total number.2 So our examination starts with two questions: Who became artists? What factors made for flourishing artistic centers?

Celebrating Human Knowledge

A series of hexagonal reliefs set into the campanile, or bell tower, of Florence’s cathedral celebrated the breadth of human knowledge, including the mechanical and liberal arts. Authorship of the panels remains debated; Andrea Pisano may have executed them in part, perhaps following designs by Giotto. These two reliefs, showing a painter and sculptor at work, indicate recognition of the important civic position of artist and artisan, already in the fourteenth century.