Milan was a large city with extensive territory, and it was rich. Patronage there was conducted on a grand scale. It helped cement the position of the Sforza, whose claim to rule rested on tenuous grounds. The first Sforza duke, Francesco, assumed the title through his marriage to the illegitimate daughter (and only child) of the last Visconti lord, whose family had governed Milan since the mid-fourteenth century. When Francesco’s son, Galeazzo Maria Sforza, made his spectacular entry into Florence in 1471, he was accompanied by 1,250 elaborately costumed courtiers and more than 1,000 horses, all wearing the Sforza colors of white and deep red. He also brought dogs and falcons. The Florentines were impressed at the display but somewhat taken aback by the excess. Galeazzo Maria had gone to Florence to cement relations with the Medici.

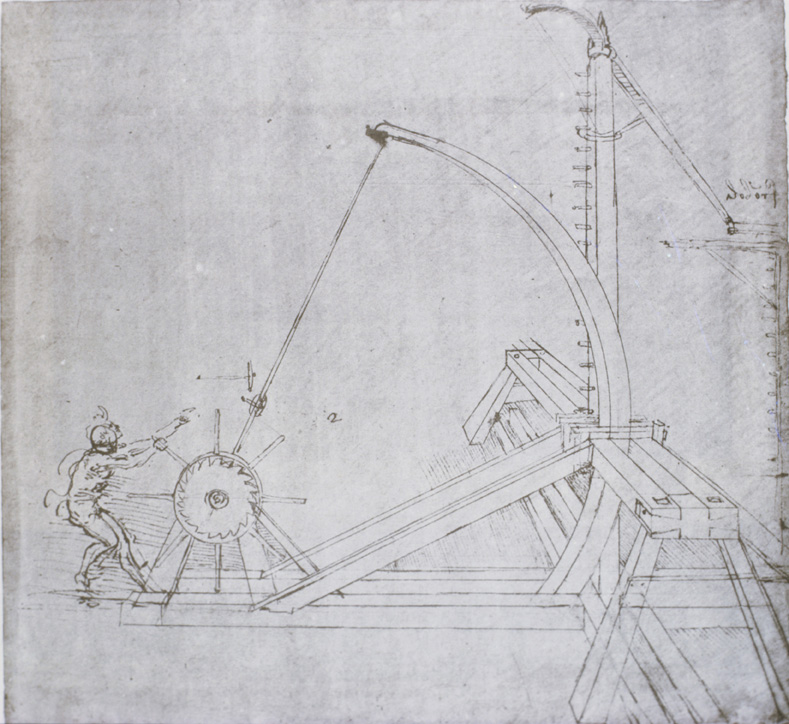

Through this connection to the Medici, the Sforza obtained the services of the most famous and versatile artist to work in Milan. Legend has it that around 1482 Lorenzo de’ Medici sent Leonardo da Vinci to present Ludovico Sforza with the gift of a silver lyre—the artist was an accomplished player. In a letter written a couple of years later, Leonardo himself laid out the skills he could offer the Sforza duke: he could design and build bridges and ladders that could be carried by soldiers to the battle field, siege machinery, projectiles, “and other machines of marvelous efficacy and not in common use” (“Leonardo lists his skills”). These talents as a military engineer, he rightly considered, were of particular interest to Ludovico. Leonardo mentioned his ability as a painter only in passing.