Barnaba da Modena

Adoration of the Child, c. 1380

Oil on wood panel

Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan

SuperStock

The Crucifixion scenes illustrate the fundamental constraints placed on narrative painting by the insistent two-dimensionality of medieval pictorial space. The shallow settings lend themselves to the depiction of only one moment in time, with little scope to suggest what happened just before or may happen next. Attempts by medieval artists to represent a sequence of events often resulted in crowded compositions and confusing juxtapositions. In Barnaba da Modena’s Adoration of the Child, for example, angels announce Christ’s birth to shepherds who already appear to have arrived at the manger, standing just behind the Virgin Mary rather than in distant fields. Their slumbering flock and sheepdog are placed equally ambiguously, sharing the foreground with Jesus’s father, Joseph. Unlike a verbal narrative, which may continue to add incident upon incident—conceivably infinitely—until the entire story is told, a physically finite painting can accommodate only a limited number of occurrences without losing clarity. To expand a painting’s narrative capacity, the space in which action takes place must likewise be developed.

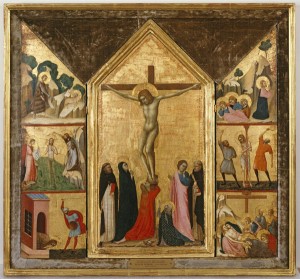

Attributed to Lippo di Benivieni

The Crucifixion with Scenes from the Passion and the Life of St John the Baptist, c. 1315–20

Tempera on wood panel, dimensions by panel: 63.5 x 17.5; 63.5 x 34.3; 61 x 16.5 cm (25 x 6 7/8; 25 x 13 1/2; 24 x 6 1/2 in.)

Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Gift of the Samuel H. Kress Collection

In the fourteenth century such expansion took physical form, with the change from single-panel paintings to more complex, composite structures known as polyptychs (often altarpieces). Physical additions, such as wings at the side and predella panels at the base, enlarged the pictorial field, providing auxiliary areas that could be used to incorporate narratives that complement or comment on the subject of the central panel. The Crucifixion in an early fourteenth-century triptych (attributed to Lippo di Benivieni), gains an enriching narrative context through the addition of two framing wings. First drawn to the large central scene, we begin to read the narrative program toward the end of the story—at the climactic moment of Christ’s death on the cross. Thematic importance rather than chronological order has determined the centrality of the Crucifixion within the triptych’s narrative program. As in a flashback, we then move our eyes to earlier chapters, turning our attention to the six small scenes that frame the Crucifixion. These episodes from the life of Christ and his precursor Saint John the Baptist establish the larger narrative context of Christ’s sacrifice. Laid out in chronological sequence, they are meant to be read from top to bottom on the left and then from top to bottom on the right.

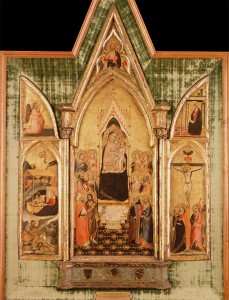

Follower of Bernardo Daddi

The Aldobrandini Triptych, c. 1336

Tempera on wood, 95.5 x 66 cm (37 1/2 x 26 in.)

Portland Art Museum, Gift of the Samuel H. Kress Collection

The predetermined, serial processing of these images mimics the orderly manner of reading words in a verbal text. As with other narrative programs, the incidents depicted in this triptych were selected and positioned in such a way as to convey certain themes and tell a particular story. Alternative arrangements produced different themes and stories. The Crucifixion scene in The Aldobrandini Triptych, by a follower of Bernardo Daddi, is relegated to a less prominent role as one of three episodes relating to the incarnation of the holy spirit in Jesus Christ. At upper left the archangel Gabriel announces that the son of God will be born unto Mary, who appears at upper right. At lower left that promise is manifested in the Nativity of Christ; at lower right the incarnation achieves its ultimate purpose with the bodily sacrifice of Christ, which redeems the sins of the world. Representing the Virgin and Child enthroned in heaven, the climactic central panel establishes the narrative program’s full meaning, slanting the story away from Christ and toward Mary and her exceptional role in the redemption of mankind as the mother of God.