Paolo Veneziano

The Coronation of the Virgin, 1324

Tempera on panel, 99.1 x 77.5 cm (39 x 30 1/2 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

The antique specimens collected by Renaissance artists attest to their fervid interest in Greek and Roman modes of representing the human body. In addition to providing artists with specific, quotable motifs, these workshop tools clearly served a more general, instructional purpose, shedding light on the classical interpretation of human anatomy. How else can we explain the stockpiles of fragmentary body parts amassed in artists’ studios, such as the sixty-three plaster casts of heads, feet, and torsos inventoried in the workshop of the Florentine painter Fra Bartolomeo.

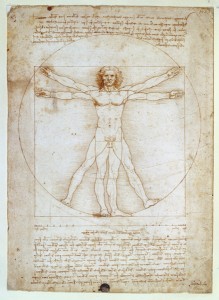

The Renaissance preoccupation with the body presented a stark contrast to medieval tradition. Valuing spirit over flesh, medieval artists had worked in an abstract, two-dimensional linear style that deemphasized corporeality. Unsatisfied by this approach, fifteenth-century artists emulated the body-conscious quality of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture, drawing inspiration from the prevalent depiction of nudity and the use of drapery as a means of articulating the body, simultaneously revealing and concealing the torso and limbs. According to classical authors such as Pliny and Vitruvius, the ideal beauty of ancient art was achieved by adapting natural forms to a perfected system of mathematical ratios. Known as the classical canon of proportion, this system became a subject of tremendous fascination to Renaissance artists who endeavored to unlock its secrets through analysis of ancient texts and surviving works of art.

Andrea Mantegna or follower, possibly Giulio Campagnola

Judith with the Head of Holofernes, c. 1495/1500

Tempera on panel, 30.1 x 18.1 cm (11 7/8 x 7 1/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Widener Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

The figural style of Andrea Mantegna exemplifies the profound affect of ancient models on Renaissance depictions of the human body. Raised in the university town of Padua, Mantegna developed a distinctly intellectual and archaeological approach to antiquity. (Read A treasure hunt for antiquities.) Over many years, he assembled an impressive collection of Greek and Roman sculpture, which he displayed in the central circular courtyard of the pseudo-Roman house he built in Mantua. Through close study, Mantegna derived insights into the formal principles responsible for the beauty of ancient art. These insights enabled him to make the classical style his own, adaptable to any subject, including Christian themes. In Mantegna’s work, the gods and goddesses of antiquity are often resurrected as Christian saints and Old Testament heroes.

Roman, 2nd century CE, after the Aphrodite of Cnidus by Praxiteles (4th century BCE)

The Toilet of Venus (Venus Felix and Cupid)

Marble, h. 214 cm (84 3/10 in.)

Museo Pio Clementino, Vatican Museums, Vatican State

Scala/Art Resource, NY

Numerous depictions of the biblical heroine Judith by Mantegna and his followers are inspired by Venus Felix, a sculpture in the Vatican’s Belvedere courtyard that the artist apparently saw during a visit to Rome in 1488 to 1490. Venus’ pose and her relationship to the smaller figure of Cupid provided the springboard for Mantegna’s composition, which shows the Jewish heroine depositing the severed head of her people’s oppressor, Holofernes, in a sack held by her maidservant. Judith adopts Venus’s pivoting, asymmetrical stance—a position known as contrapposto—which was favored by artists in antiquity as a means of lending ease and movement to statuary. Judith’s clinging drapery articulates and accentuates the torsion of her body, zigzagging energetically across her twisting waist and hips, stretching tautly over her raised thigh, and cascading in ripples down her supporting leg. Judith also appears to approximate the idealized canon of proportion that underlies the Venus statue, with each body part related to the whole by means of a fixed mathematical ratio.

15th or 16th century cast, after an ancient model

Diomedes and the Palladium

Bronze/dark brown patina, 5.1 x 4.1 cm (2 x 1 5/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

The hard-edged precision of Mantegna’s style suggests the influence of other antique models—coins, medals, and carved gems. These diminutive objects were no less important than full-scale statuary as conduits for the transmission of the classical style. Greek and Roman chalcedonies were particularly influential. The small, semiprecious gems were carved with either an incised design (intaglio) or a raised relief (cameo). Ancient gems were rare and expensive, but from the mid-fifteenth century, copies became widely available and affordable in the form of bronze plaquettes. Readily reproduced and easily circulated, plaquettes functioned in a manner analogous to prints. Small enough to be carried in a pouch or passed from hand to hand at humanist gatherings, they contributed significantly to the dissemination of classical imagery.

Attributed to Gian Francesco de’ Maineri

Saint Sebastian, c. 1500

Oil on wood panel, 33.7 x 22.2 cm (13 5/16 x 8 3/4 in.)

Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Gift of the Samuel H. Kress Collection

Diomedes and the Palladium, a Roman gem modeled on a Greek chalcedony intaglio of the first century BC, became widely known through a variety of Renaissance copies. In his Commentarii on the fine arts (c. 1450), the renowned Florentine bronze-caster and goldsmith Lorenzo Ghiberti described the gem as “the most perfect thing I ever saw.” Calling attention to anatomical adjustments used to enhance the figure’s three-dimensionality, he noted that “the foot placed on the ground was foreshortened with such art and mastery that it was a wonderful thing to see.” Ghiberti also observed anatomical adjustments made by the antique artist to idealize the nude form so that it displayed “all the measurements and proportions any carving or sculpture should have.”3

After Leochares

Apollo Belvedere, c. 120–140 CE (rediscovered late 15th century)

Marble, Roman copy of an Hellenistic bronze original made in c. 350–325 BCE, h. 224 cm (88 in.)

Cortile del Belvedere, Museo Pio Clementino, Vatican Museums, Vatican State

Vanni/Art Resource, NY

Appreciation for the ideal treatment of the body in such antiquities as Diomedes and the Palladium inspired Renaissance painters to try their hand at depicting classical nudes. Saint Sebastian, a painting of c. 1500 attributed to Gian Francesco de’ Maineri, reproduces the ideal proportions and asymmetrical contrapposto stance that Renaissance artists admired in ancient sculpture. Indeed, the martyred saint resembles a classical sculpture made flesh. Gian Francesco cultivated this resemblance by placing the figure before an arched niche, a common mode of displaying antique statuary during the Renaissance. A niche of this kind was designed specifically for one of the most influential antique statues known in the fifteenth century, the Apollo Belvedere, when the great collector Giuliano della Rovere transferred it from his private garden to the more accessible Belvedere palace following his election as Pope Julius II in 1503.