Throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance, painters’ guilds across Europe were commonly named after the evangelist Saint Luke: in Rome, for example, the guild was called the Compagnia di San Luca. This custom grew out of a tradition that the evangelist had painted the Virgin and infant Jesus from life. Images associated with Saint Luke had enormous authority.

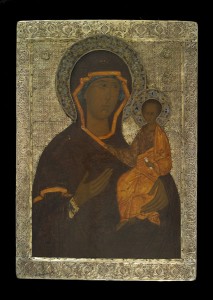

Saint Luke Painting the Virgin

El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos)

Saint Luke Painting the Virgin, before 1567

Tempera and gold on canvas attached to panel, 41.6 x 33 cm (16 3/16 x 12 7/8 in.)

Benaki Museum, Athens

© 2012 by Benaki Museum, Athens

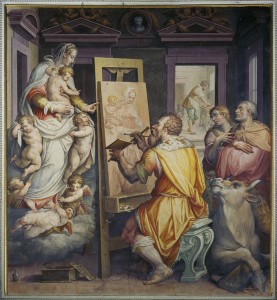

Giorgio Vasari

Saint Luke Painting a Portrait of the Madonna (Self-portrait), after 1565

Fresco

Santissima Annunziata, Florence, Italy

Scala/Art Resource, NY

Depictions of Saint Luke painting the Virgin were themselves popular. The two examples here were probably painted within two years of each other, yet their styles are worlds apart—pointing to differing conceptions of the painted image in Byzantine and Western traditions. The first work is an icon by Domenikos Theotokopoulos, better known as El Greco. El Greco had trained and worked as an icon painter in his native Crete before he left to study Western-style painting in Venice and Florence. The second, a fresco in the church of Santissima Annunziata in Florence, is by the Italian mannerist artist Giorgio Vasari, who painted himself as Saint Luke.

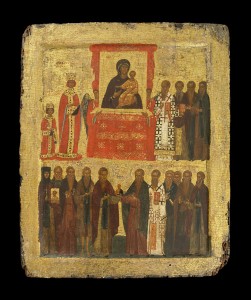

Around the twelfth century one icon in particular came to be identified with Luke’s image: a half-length portrait of Mary holding the child and pointing toward him as the way of salvation. Known as the Hodegetria—she who points the way—the original icon was taken in the fifth century to the Byzantine capital, Constantinople, and installed there in the Hodegon monastery. It was said to produce miracles daily and became such a part of the city’s life that it was carried out of the church every Tuesday so it could be seen by the public. A Spanish visitor in 1403 described how “all . . . make their prayers and devotions with sobbing and wailing” before it.4 The original Hodegetria seems to have vanished following the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. Copies of the icon, however, could be found everywhere from Russia to Ethiopia; some six hundred were known in Rome.

Icons with the Virgin Hodegetria

The Hodegetria can be recognized in El Greco’s painting of Luke and in the Triumph of Orthodoxy icon. The still elegance of its line, the abstracting quality of its gold background and striations (lines) in the drapery, Jesus’s confronting gaze—are all characteristic of Byzantine icons.

Rome also boasted at least ten icons believed, like the Hodegetria, to have been painted by Saint Luke’s own hand. These deeply venerated icons were often the focus of religious festivals and carried in procession. They were believed to work many types of miracles, not only delivering worshipers from plagues and natural disasters but also granting victory to cities in war and snatching young children from certain death. One such image attributed to Luke is the Virgin of S. Maria del Popolo. The icon was housed in the pope’s private chapel in the Lateran Palace until, after miraculously ending a plague epidemic in 1231, it was transferred to the church of S. Maria del Popolo, where it remains.

Madonna and Child (Salus populi romani)

Tempera on panel, 117 x 79 cm (46 1/10 x 31 1/10 in.)

S. Maria Maggiore, Rome

Alinari/Art Resource, NY

Another painting thought to have been made by Luke still resides in Rome’s S. Maria Maggiore. Devotion to it, and its powers, was so great that it became a symbol of the city and was eventually called the Salus populi romani (salvation of the Roman people). The S. Maria Maggiore icon was almost surely made in the late twelfth or early thirteenth century. That it greatly postdated any work ever painted by Saint Luke did not diminish it—it commanded the same authority as his original. In fact, copies of the venerated images “by Luke” proliferated. Melozzo da Forlì, for example, copied the Virgin of S. Maria del Popolo around 1460 for his patron Alessandro Sforza. Roman painter Antoniazzo Romano made something of a specialty of reproducing Luke’s icons in the 1470s. All the copies, even the crudest, were regarded as equally efficacious in performing miracles because all shared the potency of the original.