The portraits and self-portraits of several of the artists discussed in this unit are presented in this last section in roughly chronological order. Like all portraits, they speak to character, status, identity, and other aspects well beyond physical appearance.

Leon Battista Alberti

Leon Battista Alberti

Self-portrait, c. 1435

Bronze, 20.1 x 13.6 cm (7 15/16 x 5 5/168 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

Alberti was among the most talented and multifaceted of all “Renaissance men.” He produced extremely influential treatises, not only on painting but also on sculpture and architecture as well as family life. He knew law, philosophy, and the classics—he wrote a Latin comedy—and was interested in subjects ranging from ancient ships to cryptography. He worked as an architect and sculptor and made this self-portrait. His emblem, the winged eye that appears at the lower left, refers to the all-seeing eye of God. Alberti described the eye as the swiftest, most powerful, and worthy part of the human body.

Lorenzo Ghiberti

Lorenzo Ghiberti

Self-portrait, detail from the east Baptistery doors (The Gates of Paradise), 1424–52

Bronze, diameter approx. 5.8 cm (2 3/10 in.)

Baptistry of San Giovanni, Florence

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY

Ghiberti was a goldsmith, sculptor, and architect as well as the author of a commentary on art and artists. In that text he included his own biography—the first artist’s autobiography of the Renaissance. Victor in the competition to design the reliefs for the bronze doors of Florence’s baptistery, he incorporated this self-portrait in a framing panel. Both portrait and biography are testimony to the increasing status of artists.

Sandro Botticelli

Sandro Botticelli

Adoration of the Magi, c. 1473

Tempera on panel, 111 x 134 cm (43 7/10 x 52 4/5 in.)

Uffizi, Florence

Alfredo Dagli Orti/The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY

Vasari noted more than ninety instances where artists had inserted their own images into a larger scene. In Botticelli’s Adoration of the Magi, we find the artist in company with members of the Medici family, who are portrayed as the three kings. Botticelli’s outward glance (far right), which makes a direct connection between the religious actors and the viewer, is a feature of many embedded self-portraits.

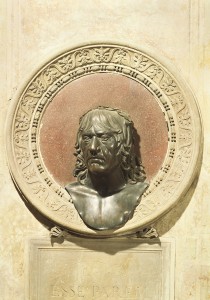

Andrea Mantegna

Attributed to Andrea Mantegna or Gian Marco Cavalli

Funerary Monument of Andrea Mantegna, installed by 1516

Bronze on porphyry framed by Istrian stone

Chapel of San Giovanni Battista, S. Andrea, Mantua, Italy

Scala/Art Resource, NY

This striking bust of Mantegna, who was known mostly as a painter but who also made sculpture, is part of his own funerary monument. It is filled with references to ancient art, which he studied assiduously. The bronze bust already copies an ancient form and bronze is the noblest material of ancient sculpture. It is placed before an ancient porphyry disk set within a frame carved with classical motifs. The circular form echoes Roman clypeate portraits. The inscription below, in Latin, reads, “you who see the bronze likeness of Aeneas Mantegna know that he is equal if not superior to Apelles.” Not only is reference made to the most celebrated painter of ancient Greece, but the artist’s own name, Andrea, has also been shifted to recall the greatest of Roman heroes.

Perugino

Perugino

Self-portrait (detail from a fresco decoration), c. 1500

Collegio del Cambio, Perugia

Alfredo Dagli Orti/The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY

When Perugino included his portrait as if hanging on the fictive architectural framing in the fresco decoration of the Collegio del Cambio in Perugia, artists’ self-portraits conceived as independent paintings hardly existed. Earlier artists had mostly painted themselves as spectators within a larger scene—as, in fact, Botticelli had previously done.

Below this image an inscription, written in antique fashion, identifies Perugino as the author of the frescoes. It goes on to suggest that if painting had not been invented, he would have created it, or he would have restored the art had it been lost. Perugino was at the height of his fame at the time, and the panegyric is fulsome, yet his image is far from grandiose.

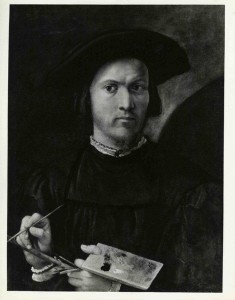

Franciabigio

Franciabigio

Self-Portrait, c. 1516

Painting on wood, 57.8 x 44.4 cm (22 3/4 x 17 1/2 in.)

Sara Delano Roosevelt Memorial House, New York, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Franciabigio, son of a linen weaver, operated a joint workshop in Florence with Andrea del Sarto. The square palette the artist holds was typical of his time.

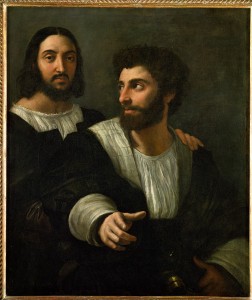

Raphael

Raphael

Raphael (self-portrait) and His Fencing Master, c. 1518

Oil on canvas, 99 x 83 cm (39 x 32 7/10 in.)

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Erich Lessing/Art Resource,

In this double portrait—a type fairly uncommon in the Renaissance—Raphael paints himself with a young man who holds a sword at his side. Early descriptions sometimes refer to the younger man as the artist’s fencing master, but that identity is questionable given that his fine dress and sword are signals of his aristocratic status. He is likely to have been a friend of high rank. Raphael, however, depicts himself in a position of superiority, standing above his companion and placing a proprietary hand on his shoulder.

Bandinelli

Niccolò della Casa

Portrait of Bandinelli, c. 1540–5

Engraving, 29.2 x 22 cm (11 1/2 x 8 11/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

Bandinelli is mentioned only briefly in this unit, as the founder of an early academy, but he is illustrated here because he is one of a small group of Renaissance artists who depicted themselves many times—in Bandinelli’s case some twenty-five times, far in excess of the eight self-portraits known by Titian, the six by Vasari, and the four each by Mantegna and Raphael.

In this image he is finely dressed and wears the insignia of the Order of Santiago. He points, literally, to his profession as a sculptor. With one hand Bandinelli directs our attention to the contour of the figure—reminding us of the importance of disegno as the foundation of sculpture.

Daniele da Volterra

Daniele da Volterra

Portrait of Michelangelo, c. 1545

Oil on panel, 88.3 x 64.1 cm (34 3/4 x 25 1/4 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

Daniele da Volterra painted the head and hand of Michelangelo with fine detail and left the form of the body only roughly suggested. Is it unfinished on purpose? Perhaps. The head and the hand point to the two overriding sources of art: the intellect that conceives it and the hand that executes it. Daniele may also have been alluding to Michelangelo’s own habit of leaving many works unfinished—because, as Vasari explained, Michelangelo’s hand could not translate the awesome concepts his mind produced.

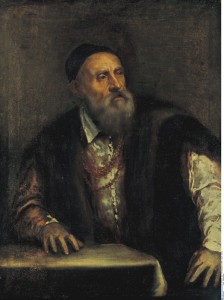

Titian

Titian

Self-portrait, c. 1560

Oil on canvas, 96 x 75 cm (37.8 x 29.5 in.)

bpk, Berlin/Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen, Berlin, Germany/Joerg P. Anders/Art Resource, NY

Here Titian wears the rich satins and fur of a patrician, a heavy gold chain looped across his chest. In 1533, Charles V appointed him Count Palatine and raised him to the rank of a Knight of the Golden Spur. Titian was probably the first visual artist ever to have been awarded such an honor by a monarch. It gave him the right to wear a sword and spurs.

Not surprisingly, since Titian was the greatest court painter of his day—called the painter to popes and princes—he was also an accomplished courtier. Lodovico Dolce, a contemporary, described him thusly: “He is a brilliant conversationalist, with powers of intellect and judgment which are quite perfect in all contingencies, and a pleasant and gentile nature. He is affable and copiously endowed with extreme courtesy of behavior. And the man who talks to him once is bound to fall in love with him forever and always.”16

Sofonisba Anguissola

Sofonisba Anguissola

Self-portrait, Painting the Madonna, 1556

Oil on canvas, 66 x 57 cm (26 x 22 2/5 in.)

Muzeum Zamek w Lancucie, Lancut, Poland

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY

Sofonisba Anguissola painted more self-portraits than most other artists of her time, man or woman: at least twelve are known. This one served as a kind of advertisement of her skill as an artist, especially as a portrait artist. Perhaps because of her noble origin she did not shy away, as many men painters did, from showing herself at work, her hands occupied with brush and mahlstick. Other self-portraits show her at a keyboard or reading, evidence of her suitability as a courtier—a beautiful woman who was well educated and skilled in all the accomplishments expected of well-born ladies.