In the late fifteenth century, a few institutions that emphasized learning and knowledge over technical skill began to appear. Francesco Squarcione established a “studio” in Padua around 1440, perhaps the first to operate outside the guild and workshop system. It seems, however, that Squarcione coerced, even adopted, his most talented pupils (including Andrea Mantegna) for financial gain. His later reputation as a teacher may rest more on their success than on his innovative way of training artists.

Some forty years later the so-called Medici Academy was created in Florence, under the sponsorship of Lorenzo de’ Medici. It was administered by sculptor Bertoldo di Giovanni, a Medici favorite. Artists and young patricians met at a property the Medici owned around the Piazza San Marco—a pleasant retreat with rooms, loggias, and a garden where works from Lorenzo’s collection of ancient sculpture were displayed (although the finest were probably kept in the Medici palace). The sculpture garden was of sufficient interest to be highlighted on some early topographical views of Florence. The original “Academy,” the one created by Plato in the fourth century BCE, had met in a sacred grove outside Athens, a connection that Lorenzo and his humanist circle would not have overlooked as they sought to style their city a new Athens.

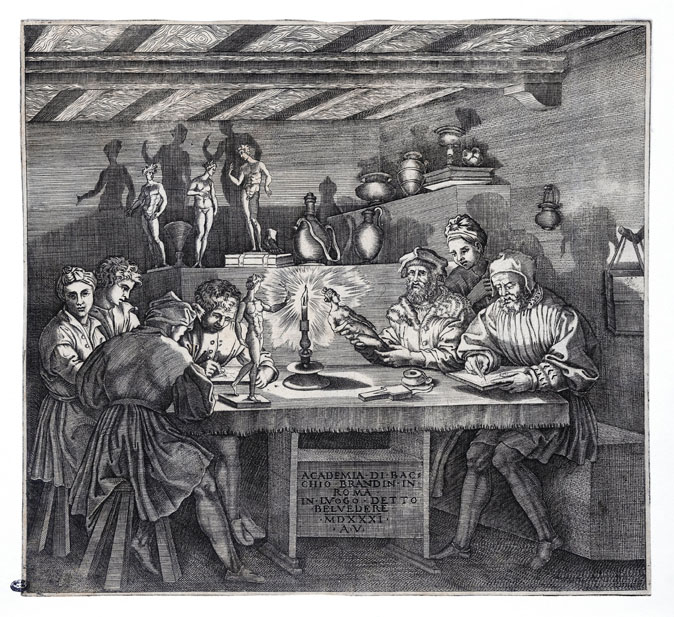

Lorenzo de’ Medici in the Sculpture Garden

Designed by Johannes Stradanus

Lorenzo de’ Medici in the Sculpture Garden, 1571

Tapestry, 425 x 455 cm (167 5/16 x 179 1/8 in.)

Museo Nazionnale di San Marco, Pisa

Soprintendenza alle Gallerie, Florence

This tapestry, designed by Johannes Stradanus, shows Lorenzo seated in his garden surrounded by antique busts and young artists at work. The Flemish Stradanus (called Giovanni Stradano in Florence) worked for Cosimo I de’ Medici’s tapestry works and was an officer of the Accademia del Disegno. This is part of a set of tapestry designs he did under Vasari’s direction for the Medici’s Palazzo Vecchio. The decoration in various rooms celebrated different Medici ancestors.

Information about Lorenzo’s sculpture garden is sparse, but it figures in two stories circulated about the young Michelangelo. One had the youth so impressed by the works of ancient sculptors he saw there that he abandoned his training as a painter on the spot, never returning to the shop of Ghirlandaio, where he had been apprenticed. The Michelangelo biographer Ascanio Condivi also recounts how the youth had taken up an unworked block and perfectly copied an antique head of a faun, impressing and amazing Lorenzo. Here, in one stroke, Michelangelo began his career as a sculptor and his long association with the Medici. Such accounts must be viewed with some skepticism, however, since Condivi, who took his cues and much of his actual text from the artist himself, continually underplayed Michelangelo’s artistic training to increase the sense of the master’s unique genius. Nor did either the artist or his biographer overlook any opportunity to underscore a Medici connection.

Vasari provided the most extensive description of the garden and named its pupils (see “Giorgio Vasari’s description of the Medici ‘academy’”)—but he had motives of his own. As the major force behind the Accademia del Disegno (see below), Vasari was interested in giving that later organization a pedigree, especially one that could link it both to Michelangelo, in whom Vasari saw the perfection of art in his time, and to the illustrious ancestor of his own patron, Cosimo I de’ Medici. Lorenzo’s sculpture garden can probably be viewed as a proto-academy at best. Nevertheless, Lorenzo was certainly active in promoting the arts, visual and literary, in his city. Vasari said that Lorenzo had opened the garden to remedy a shortage of sculptors in Florence. It is also clear that he pushed sculpture in the direction of classical art. It has been suggested that some work carried out in the garden involved restoration of antique statues. By encouraging students to draw after antique models, Lorenzo provided a sort of training not always available in the city’s traditional workshops and enhanced Medici prestige through progressive patronage of the arts.

While Leonardo da Vinci was in Milan in the 1490s, he was part of the “Academia Leonardi Vinci.” Its members included literary men, other artists, and musicians—a document from 1513 described it as the “forge and hearthstone of the wise.”6 Rather than a forum for instruction, however, it seems to have been an informal association of people with shared enthusiasms. The sculptor Baccio Bandinelli also assigned the label “academy” to his studios, initially in Rome in the 1530s and later in Florence. But the first true academy, an institution with official status organized to provide art students with a formal educational program, seems to have been the Accademia del Disegno in Florence.

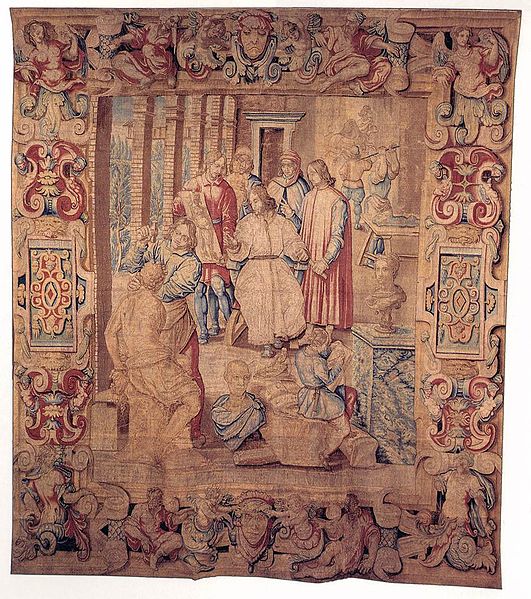

Fourth Knot

After Leonardo da Vinci

Fourth Knot, c. 1490/1500

Engraving (the five parts of the knot are cut out from the sheet and trimmed to the image), diameter 20.7 cm (8 1/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Rosenwald Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

Little evidence about the Academia Leonardi Vinci survives. The name appears in a series of six engravings with intricate interlacing patterns. Vasari said that Leonardo was wont to “waste his time” designing ornate knots. The plates for these, probably cut by assistants, were perhaps meant for book illustrations. It has been suggested that the knots refer to Leonardo himself or at least to his name—the similar word vincoli means chains or fetters—but knot designs appear in the works of many artists.

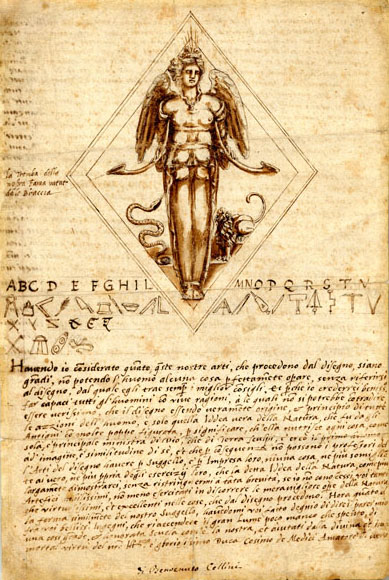

Bandinelli and His Students

The 1531 print depicts Bandinelli and students in Rome, with an inscription referring to the assembly as an “academy”; the second print, from the 1550s, shows the later establishment in Florence, where various parts of human skeletons are available for study. Anatomy was considered a particular skill of Bandinelli’s. In the Rome image, candlelight throws dramatic shadows on the walls, as students draw from ancient statuettes or casts. The pairing of silhouettes with their three-dimensional sources offers a concrete illustration of how drawing or painting and sculpture are related to each other through disegno.

Duke Cosimo granted a constitution to the Accademia on January 31, 1563. Its origin lay a few years before, when the monk and sculptor Fra Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli (one of Michelangelo’s pupils) dedicated the crypt he was building for himself in the convent of the church of Santissima Annunziata for the common use of all practitioners of the arts of disegno—painters, sculptors, and architects—who died without a burial place; he also provided for masses to be said for their souls. Vasari saw Montorsoli’s endeavor as an opportunity to retool the old, now moribund, Company of Saint Luke (see Guilds) into a new organization that, beyond its religious function, could promote the intellectual and theoretical education of young artists while further distancing them from traditional trades and the guilds. The group first convened in 1562 to rebury the remains of Pontormo, who had died in 1557. The new sepulchre was sealed by a stone with reliefs depicting the tools used by artists and architects.

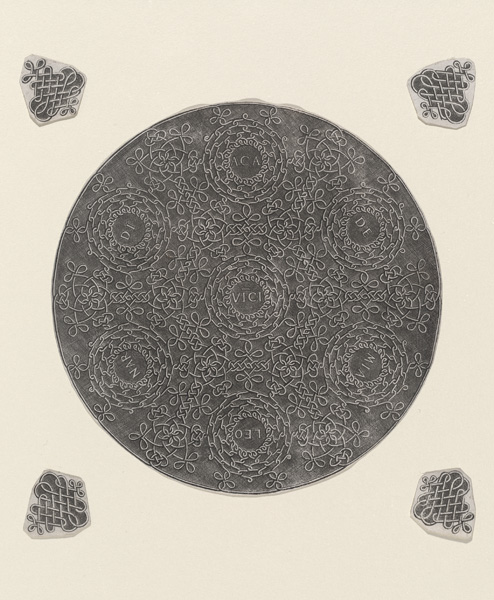

Accademia del Disegno

Benvenuto Cellini

Design for an emblem for the Accademia del Disegno, c. 1562

Pen and brown wash, 33 x 21.8 cm (13 x 8 9/16 in.)

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Duke Cosimo called a competition for the design of a new impresa (emblem) for the Accademia. This design is one of several that Cellini made (though not the one he finally submitted). The long inscription helps explain the image. The figure is the famous ancient statue of Diana from Ephesus, with wings of inspiration added. She is flanked by a snake, a symbol used by Cosimo, and a lion, a symbol of Florence. From the arms of the goddess extend flaring trumpets—to herald the fame of art and artists. An “alphabet” of artists’ and architects’ tools parallels the letters used by poets and philosophers just above. In fact, the Accademia continued for many years to use the winged bull, symbol of Saint Luke, which had been the emblem of the old Company of Saint Luke. The new design eventually adopted consisted of three interconnected wreaths for the three arts of painting, sculpture, and architecture.

When the new Accademia (officially the Compagnia e Accademia del Disegno, a name reflecting its origin and continued role as a lay confraternity) was formally constituted the following year, Cosimo was made capo (head), forestalling any possible objection from the guilds. For the duke, this was an opportunity to bring the visual arts closer into the fold of the state, just as he had done with the humanities. With a small territory, a small army, and a short aristocratic history, Cosimo, like Lorenzo before him, used culture to enhance his prestige. (It worked: when the French royal academy of the arts was formed under Louis XIV in 1648, the first paragraph of its charter referred specifically to the patronage of the dukes of Tuscany.) Cosimo shared the title of capo with Michelangelo, who was then quite old and had not been in Florence for thirty years. But he was still revered: no one had more perfectly applied the ideals of disegno or done more to elevate the image of the artist. The standing of the Accademia was greatly enhanced by one of its earliest and most public projects—the staging of Michelangelo’s elaborate funeral in 1564, which celebrated the genius of one artist and all art. The Accademia was administered by Vincenzo Borghini, humanist and historian—and not coincidentally a friend of Vasari’s. Borghini did as much (or more, some argue) as the artist to shape the new organization, and he was close to the duke.

The statutes of 1563 laid the groundwork for the Accademia’s educational program, which offered regular lectures on geometry and other subjects and periodic demonstrations of anatomy. Academy members visited young artists in the workshops where they apprenticed to offer encouragement and suggest improvements to their work. Students without money were given financial support.

The Accademia became the most important art institution in Florence in the late sixteenth century. Records show that its membership included almost every artist working in the city; among the officers were Vasari, Benvenuto Cellini, Giambologna, and other leading practitioners. Members did not have to be Florentine—Giambologna, for example, was born and trained in the Low Countries. A plan to admit amateurs as well as practicing artists was discussed but abandoned. In the seventeenth century, however, “gentlemen and noble persons [who] are knowledgeable with respect to the sciences of architecture and the art of disegno” did participate.7

In 1571 the Accademia petitioned Cosimo to formally release painters from the Arte dei Medici e Speziali, and sculptors from the Fabricanti (which had superseded the Arte dei Maestri di Pietra e Legname). Thereafter the Accademia assumed various guild functions and was finally incorporated as a guild itself in 1584. The institution endured until the late eighteenth century, and the most important years of its history lie beyond the period under consideration here. For us, it marks an important transition in the perception of the artist and the growing acceptance of his work as being on a par with philosophy, literature, rhetoric, and the other liberal arts.

Saint Luke Painting a Portrait of the Madonna

Giorgio Vasari

Saint Luke Painting a Portrait of the Madonna (Self-portrait), after 1565

Fresco

Santissima Annunziata, Florence, Italy

Scala/Art Resource, NY

Vasari painted this fresco in the Accademia’s chapter room (which came to be called the Cappella di San Luca, partly on account of this work) in Santissima Annunziata. We see Luke, in the person of Vasari himself, painting the Virgin and Child. Looking on are Montosorli and the prior of the church. The chapel was actually dedicated to the Trinity—appropriate for the three arts of disegno but also a common focus in contemporary Counter-Reformation theology.

![Niccolò Fiorentino<br /><i>Alfonso I d'Este (1476–1534), 3rd Duke of Ferrara, Modena and Reggio (1505)</i> [obverse], 1492<br />Bronze, diameter 7.1 cm (2 13/16 in.)<br />National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection<br />Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art](http://italianrenaissanceresources.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/RP_1061-1.jpg)