Although Michelangelo was noted for doing much of the laborious work of marble carving himself, sculpture, like painting, was most often a collaborative endeavor, whether in bronze, wood, terracotta, or stone. Stone sculpture (and Italy is rich in marble) presented unique challenges, starting with the expense and logistical difficulties of transporting heavy material. Considerable engineering ability was required to construct the rigging needed to position large blocks, and sculptors had to understand the material’s capacity to support its own weight in space. Given the skills required, it is not surprising that many sculptors also worked as architects.

Assistants typically roughed out a block to be carved following drawings made by the master or a design he had sketched directly on the stone, or by transferring points from a small model the master had made in wax or clay. During the first half of the fifteenth century, sculptors in marble and bronze relied increasingly on three-dimensional models, called bozzetti, and less on drawings alone. Working with a three-dimensional form from the outset encouraged sculptors to plan their works from multiple points of view and create more dynamic and challenging poses. Bozzetti were particularly useful in explaining a planned work to a patron. Some painters used models, too. Leonardo, for example, draped them with fabric to study the fall of folds—a practice he seems to have picked up from his teacher, Verrocchio, who was himself primarily a sculptor.

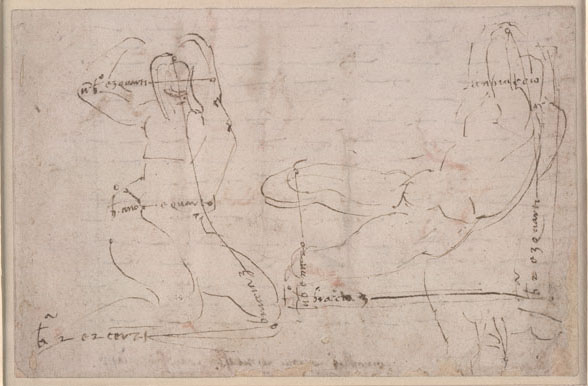

Michelangelo’s Sculptural Designs

Michelangelo

Drawings for a recumbent statue, c. 1525

Pen and ink, 13.7 x 20.9 cm (5 3/8 x 8 1/4 in.)

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Michelangelo worked up his sculptural designs in quick sketches and more detailed views, and also made bozzetti. This sketch, with measurements, was probably meant for the quarryman. It shows an early stage in planning a reclining river god, one of two that were to be part of the tomb Michelangelo created for Lorenzo de’ Medici. A clay model for the river god also exists (Accademia, Florence), but the marbles were never executed.

Giambologna

Sketch model for a river god, c. 1580

Terracotta, 31 x 39.4 x 25 cm (22 1/5 x 15 1/2 x 9 4/5 in.)

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

This bozzetto, also for a river god, was made by Giambologna, who was born more than fifty years after Michelangelo. Giambologna made more bozzetti than any other sculptor of his day for works in marble and bronze. The survival of sculptors’ models suggest that bozzetti—like drawings—had begun to be appreciated in their own right as part of the greater interest in the artist and his creative process.

Bronze statues had been the most highly prized works of art in the ancient world, but freestanding bronze sculpture was not widely produced again for many centuries. Bronze as a material for art experienced a “renaissance” of its own in the fifteenth century, not only for large-scale statuary and statuettes, but for relief plaquettes and medals. Sculptors working in bronze—an expensive and technically challenging material—often left the casting itself to professionals like the makers of bells or cannon. Assisting Ghiberti with the bronze doors for Florence’s Baptistery between 1407 and 1424 were no fewer than twenty-five men. Bronze not only required high temperatures and careful control of the casting process but also an understanding of what was technically feasible in the design and fabrication.

Finishing of sculpture, no matter the material, often involved other skills and other hands. Marble surfaces received varying degrees of polish to eliminate (or not) the marks left by carving tools. Bronzes were patinated in chemical processes that achieved surface colors, from green to lustrous browns and blacks, otherwise attained only over time as the metal oxidized. Artists routinely painted wood and terracotta sculptures, and sometimes marble as well; they might even gild unpainted marble figures to highlight details. These processes, again, were usually done by specialists.

Saint John the Baptist

Benedetto da Maiano

Saint John the Baptist, c. 1480

Painted terra-cotta, 48.9 x 52 x 26 cm (19 1/4 x 20 1/2 x 10 1/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Andrew W. Mellon Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

Benedetto da Maiano worked primarily in marble but also made terracotta sculpture, as models and as finished works like this one.

The manual labor—the sweat and grime—involved in making sculpture was one argument deployed against it in the paragone, the debate over the relative merits of painting and sculpture that became a popular trope of Renaissance (and later) writers, theorists, and artists (see Competing for Status 2).