Much of our contemporary picture of “the artist” as a misunderstood genius who chooses to stand outside a society that does not appreciate him (or her) is based on romantic stereotypes dating to the nineteenth century. This characterization, as we have seen, is not applicable to the Renaissance (although, of course, there were eccentrics like Piero di Cosimo, Rosso Fiorentino, and Pontormo). In other ways, however, it was the Renaissance that made the modern notion of the artist, and art, possible. As artists grew more self-conscious, they sought to establish for art its own set of theoretical foundations—for example, Vasari’s notion of disegno as a unifying constant and his description of artistic progress (see Drawing, Vasari, and Disegno and Vasari and Art History). The idea of art as an end in itself—art for its own sake—became imaginable.

Portrait of Andrea Quaratesi

Michelangelo

Portrait of Andrea Quaratesi, 1532

Black chalk, partly stippled, 41.1 x 29.2 cm (16 3/16 x 11 1/2 in.)

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Four versions of this portrait of Andrea Quaratesi are known. Michelangelo was reluctant to do portraits, but he was devoted to this young man, to whom the artist gave a number of his presentation drawings.

So, we find Michelangelo creating drawings, not as preparatory tools, but as finished works for presentation to friends. Important patrons such as Isabella d’Este began to look for paintings and sculpture by a particular artist simply to own his work, rather than to have a certain subject painted by him. Isabella, for example, wanted a painting by Giovanni Bellini and was willing to let him decide what it would be. He reserved the right, he told her intermediary, Pietro Bembo, “to wander at will in his pictures, so they can give satisfaction to himself, as well as the beholder.”11 At the end of our period, in the 1580s, Giambologna devised a complex sculptural group with three figures, a challenge with which Michelangelo had struggled. The work was attached to a subject only after its creation, when a colleague in the Accademia del Disegno suggested the title—Rape of the Sabine Women. Giambologna did not set out to represent Sabines; he simply made a sculpture. He wrote to his patron that the subject was chosen “to give scope to the knowledge and a study of art.”12 There was no requirement that it be justified by a story.

Rape of the Sabine Women

Giambologna

Rape of the Sabine Women, 1582

Marble

Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence

Photo by Son of Groucho (Flickr), via Wikimedia Commons

Rape of the Sabine Women was not the only title or subject proposed for Giambologna’s nameless work. Another suggestion was that it be titled as a depiction of the abduction of Andromeda.

Competing for Status 1: Art versus Poetry

“Painting is mute poetry and poetry a speaking picture.”

—Plutarch, Moralia 34613

“Painting is mute poetry and poetry is blind painting.”

—Leonardo da Vinci, Paragone14

When Plutarch, writing in the late first and early second centuries CE, linked poetry and painting, he was repeating ideas already voiced by the Greek poet Simonides, who had lived some six hundred years before. The most famous formulation of this association came to be the one made by Horace (65–8 BCE): ut pictura poesis (as is painting so is poetry). His point was that both arts merited the attentive appreciation of audiences (and that good and bad examples of each could be found). While most ancient authors used such comparisons as a way to help explain the nature of literature—and not the other way around—the very existence of these writings, given the authority ancient sources commanded for Renaissance theorists, helped propel the status of the visual arts higher. By the sixteenth century the comparison of painting with poetry was commonplace in theoretical discourse. Even Shakespeare took it up (in Timon of Athens, I, i).

It was an easy next step to consider the superiority of one art over another. In the minds of most humanists, it was literature that could most fully capture the range of emotion and the realm of the imagination. Artists, not surprisingly, took a different view. Leonardo, for example, closely paraphrased Plutarch in the quote above, but made his own opinion clear through a subtle difference in the text. Because he saw sight as the most noble of the senses, Leonardo judged painting to be superior to poetry, which was recited and heard fleetingly. He accorded painting, which he held to be a science because it was based on a principle (perspective), a place just after geometry and before astronomy and optics (see “Leonardo on painting versus poetry”).

Competing for Status 2: Painting versus Sculpture (Paragone)

The paragone—a frequently argued debate between partisans of painting and those of sculpture—was an extension of the older question about the relation of art and poetry. Painters noted early on that they were of a station above average workers or artisans since they could wear nice clothes instead of rough smocks or aprons while they worked. (It is not clear how many actually did so; though painters’ self-portraits routinely show them finely dressed, most probably wore more practical garb.) In this distinction, painters saw an advantage over sculptors: fine clothes were not an option in the arduous job of carving stone or the messy one of building up clay or plaster models.

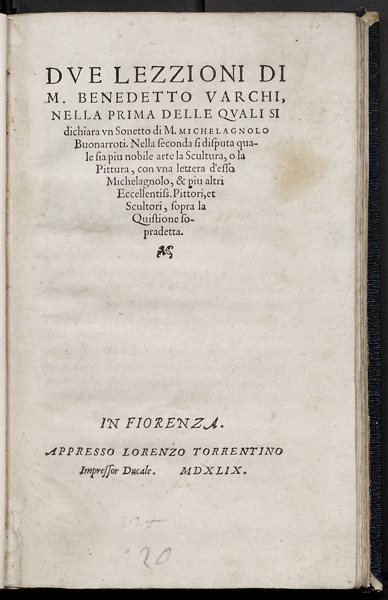

Due Lezzioni di M. Benedetto Varchi

Title page from Due Lezzioni di M. Benedetto Varchi (Two Lessons of M. Benedict Varchi) Published Florence, 1549 Library, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, J. Paul Getty Fund in honor of Franklin Murphy Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

In 1543 humanist and theorist Benedetto Varchi polled a number of artists about their views on the paragone and got eight responses, which he published. To no great surprise, painters generally thought painting superior, and sculptors thought sculpture was. (Michelangelo, equally adept at both, balked at the question. He recommended that men “desist from all these disputes which take more time than does the making of figures.”15)

Sculptors argued that their work was more permanent and that a sculpted object was necessarily more “real” than a painted imitation of an object (a picture), no matter how excellently made. Painters pointed out that they had the advantage of showing colors and the effects of light and shade. Sculptors countered that only a statue could offer the viewer differing points of view. Painters responded with ingenious compositions that used mirrors and reflections to prove that argument false. Many of these claims and counterclaims appeared in the writings of Leonardo, who sided with painters over sculptors (as he had with painters over poets) (read more paragone debates, “Painting versus sculpture”) and “Leonardo on painting versus sculpture”).

A Different Point of View

Giovanni Girolamo Savoldo

Self-portrait, formerly known as Portrait of Gaston de Foix, c. 1529

Oil on canvas, 91 x 123 cm (35 13/16 x 48 7/16 in.)

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, NY

Giorgione was reported to have made a painting in which reflections offered different viewpoints of Saint George. That work is now lost, but the same idea motivated Giovanni Girolamo Savoldo. Some scholars believe this is a self-portrait; a mirror, of course, was required for an artist to paint his own likeness.

Although the arguments of the paragone may seem to us something like a pointless—if highly popular—parlor game, theoretical discussion of the visual arts elevated their standing in the firmament of the humanities by proving that visual art could support a critical vocabulary of its own.