Cennini’s thirteen-year span for the training of an artist was considerably longer than usually occurred. The statutes of different city guilds (see Guilds) often specified fewer years. In Venice an apprentice could move on to journeyman status after only two years; in Padua the minimum apprenticeship was three years, during which masters were forbidden from trying to tempt away the students of others.

Whatever the length of training, any mature artist would have mastered the skills and materials Cennini enumerated. An artist might specialize as a painter or sculptor, but he often worked as both and was frequently called on to produce works in other media as well, including such ephemera as parade shields, banners, and designs for temporary porticoes constructed for the ceremonial entrances of important visitors to a city. Titian even designed glassware.

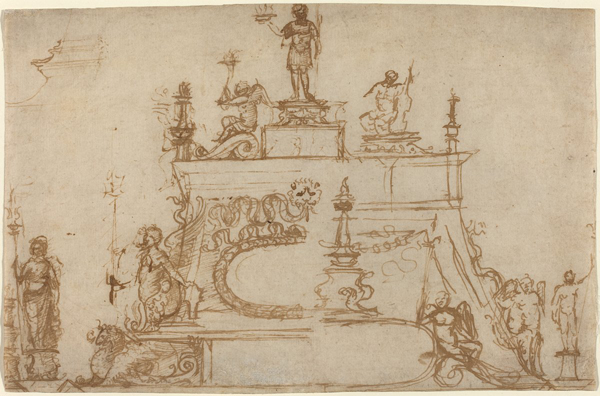

Designs for Small Bronzes

Filippino Lippi

Designs for Small Bronzes, 1490/95

Pen and brown ink on laid paper, 16.6 x 25 cm (6 9/16 x 9 13/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Woodner Collections

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

These may be sketches for small decorative objects, or, as has been suggested, preliminary designs for a triumphal chariot. Filippino created a chariot for the entry of French king Charles VIII into Florence in 1495.

Training usually began at an early age. Some boys were placed with a master before they were ten years old. Andrea del Sarto, a tailor’s son, was only seven when he was apprenticed to a goldsmith (his predilection for drawing soon prompted his move to a painter’s shop), but most boys were three or four years older than that when they began. Although some scholastic preparation continued once boys entered a shop—and most artists were literate—the young ages at which they apprenticed meant that their formal education was limited. Michelangelo was unusual in that he continued to attend school until he was thirteen, only then entering the shop of Domenico Ghirlandaio.

Boys who apprenticed in a workshop—called garzoni—typically became part of their masters’ extended household, lodging and sharing meals with the family. Parents often paid the master for their sons’ keep, but masters, in turn, were obliged to pay wages to their apprentices, increasing the wages as skills grew.

Pupils began with menial tasks such as preparing panels and grinding pigments. They then learned to draw, first by copying drawings made by their masters or other artists. Drawing collections served not only as training aids for students but also as references for motifs that could be employed in new works (see Drawing, Vasari, and Disegno). These collections were among the most valuable workshop possessions, and many artists made specific provisions in their wills to pass them down to heirs. Young artists also learned from copying celebrated works that could be seen in their own cities—Michelangelo, for example, copied paintings by Giotto in Florence’s church of Santa Croce—and they were encouraged to travel if they could, to Rome especially, to continue their visual education. When masters obtained important commissions in distant cities, assistants who accompanied them gained practical experience and exposure to new influences.

The aspiring artist’s next step was to draw from statuettes or casts. Ancient sculpture was especially valued for this purpose (see Recovering the Golden Age), and students’ study of it helped foster greater naturalism in Renaissance depictions of the human form. The practice of converting a static three-dimensional object into a two-dimensional image was a vital step before a student moved on to draw from a live model. In many cases the model was one of the shop’s garzoni, called on to assume various poses.

The Garzone

School of Filippino Lippi

Young Man (Youth Seated on a Stool), c. 1500

Silverpoint heightened with white on paper with an ochre-colored preparation, 22.2 x 16.8 cm (8 3/4 x 6 5/8 in.)

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Harriet Otis Cruft Fund

This garzone models a dramatic gesture. Shop boys posed for both male and female figures; the use of women models was extremely rare and probably limited to the master’s own wife or daughters. Vasari, who apprenticed in Andrea del Sarto’s workshop and disliked Andrea’s wife, Lucrezia, observed that every woman Andrea painted looked like Lucrezia. In this case, however, Vasari attributed the resemblance to Andrea’s devotion, not simply studio practice.

The Alba Madonna

Raphael

The Alba Madonna, c. 1510

Oil on panel transferred to canvas, diameter 94.5 cm (37 3/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Andrew W. Mellon Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

Two sketches, on the front and back of a single sheet, show how Raphael planned and perfected the figure composition of the Alba Madonna. To capture the complex and foreshortened pose of the Virgin, he (or, some believe, his student Guilio Romano) sketched a workshop assistant in the pose of the classically inspired Madonna.

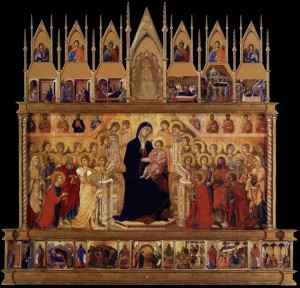

Once a student had graduated to painting, he would usually spend time executing less important parts of a composition, such as sections of landscape background. The product of a Renaissance shop was in almost all cases a collaborative effort—the substantial contributions of many people were absolutely necessary to complete a monumental work like Duccio’s two-sided altarpiece known as the Maestà, for example, or to keep pace in a busy shop like that of Neri di Bicci. The records Neri left of his workshop activity indicate that he produced an average of more than three altarpieces each year. Over the twenty-two-year span covered by his account, one scholar counted seventy-three altarpieces, eighty-one domestic tabernacles, and sixty-nine miscellaneous jobs.5

Duccio’s Maestà

Duccio

Conjectural reconstruction of the Maestà (Madonna Enthroned). (front), 1311

Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Siena

Digital reconstruction by Lew Minter

Duccio

Conjectural reconstruction of the Maestà (Madonna Enthroned). (back), 1311

Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Siena

Digital reconstruction by Lew Minter

The commission for Duccio’s Maestà specified that it be by his own hand, and Duccio signed it, but most scholars agree that many of the back panels were executed, at least in part, by assistants.

The master might paint only the central figures or simply the faces in a work—or he might not paint any of it at all. Students were trained to work in the master’s style and succeeded to such a degree that it is sometimes hard for today’s art historians to distinguish the hand of a master from that of his most talented pupils. Attributions of some paintings from the studio of Verrocchio, for example, have gone back and forth between the master and various assistants. The same confusion applies to works of Perugino (one of Verrocchio’s students) and his young assistant Raphael, and those of Giovanni Bellini’s students Giorgione and Titian. Although contracts sometimes specified that the master himself execute certain parts of a composition, guild rules allowed him to sign as his own any work that emerged from his shop. “Authenticity” in the modern sense was not at issue. A master’s signature was a sign that a work met his standards of quality, no matter who had actually painted it.

Madonna and Child with a Pomegranate

Lorenzo di Credi

Madonna and Child with a Pomegranate, 1475/80

Oil on panel, 16.5 x 13.4 cm (6 1/2 x 5 1/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

Andrea del Verrocchio was primarily a sculptor—in bronze and marble—but also worked as a goldsmith and painter. He ran one of the most successful studios of the Italian Renaissance, and some of the most important artists from the next generation trained with him, including Perugino, Lorenzo di Credi, and Leonardo da Vinci. Other painting assistants included Ghirlandaio and Botticelli.

This small panel, just over six inches tall, continues to invite debate. It reproduces Verrocchio’s style—but did he paint it? Or did Leonardo? Or is it by Lorenzo di Credi, who was Verrocchio’s favorite and took over the shop after the master’s death? Current thinking gives the nod to Credi. The first work by Credi that Vasari mentions is a Madonna having a design taken from Verrocchio; Vasari goes on to note a “far better picture,” perhaps this one, which Credi based on a composition by Leonardo. This picture has also been assigned at times to Leonardo, but Leonardo’s own colors were typically more muted than the ones used here; further, it is unlikely that Leonardo would have painted the child in this awkward and somewhat puzzling pose.

After a period of training in a shop, a student could proceed to journeyman status. Following submission and acceptance of a piece that demonstrated his mastery—the masterpiece—an artist could then open a shop and take on students of his own. Some artists never became independent masters themselves but continued to work, sometimes as temporary help for large commissions, in the shops of others. A few artists, including Andrea del Sarto and Franciabigio, formed joint workshops. For them it made business sense and, as Vasari observed, they found each other’s company agreeable.