The “Catena Map”

Lucantonio degli Uberti, after Francesco Rosselli

The “Catena Map” with view of Florence, c. 1500–1510

Woodcut in 8 blocks

Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen, Berlin, Inv. 899–100

bpk, Berlin/Joerg P. Anders/Art Resource, NY

This woodcut from around the 1470s, called the “Chain Map” for its border design, remained the basis for views of Florence for more than a century.

In the entire history of Western art, two places stand out for the sheer number of artists and the quality and innovation of their production: Renaissance Italy and the Dutch Republic of the seventeenth century. Each was the most urbanized culture of its time. Change occurs more easily in cities, where a critical mass of people and ideas converge. Industry also centers in and around cities, and it was the presence of artisans and skilled workers in some Italian cities that both furnished the pool from which most artists came and fostered the climate that supported them. Florence’s position as a leader in the wool and silk industries, for example, relied on a reputation for quality, a tradition of craftsmanship and excellence that made discerning patrons of its merchant and banker citizens. Cities with economies less oriented toward production—like Rome and Naples, which served papal and royal courts—did not produce anywhere near as many artists as Florence did, although they were important centers of artistic patronage. In the survey cited earlier, the Papal States accounted for 18 percent of the creative elites, and the whole of southern Italy, including Naples, only 7 percent. Even Venetian artists did not match the innovations of their Florentine counterparts until Venice’s economy increased its emphasis on native production (of textiles and glass, for example) and became less exclusively focused on trade in luxury goods from the East.

Arte and Ingegno

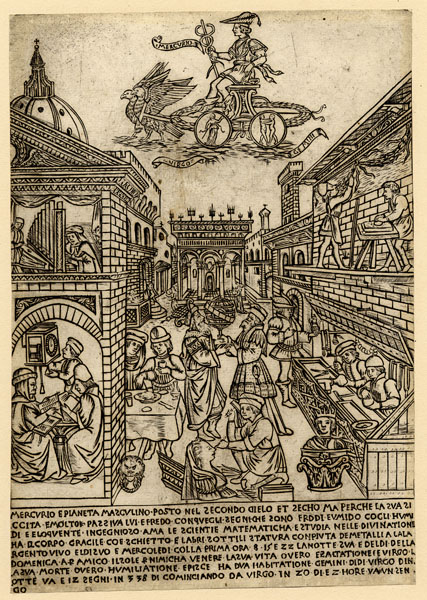

These two illustrations are from series depicting the areas of human endeavor governed by the planets. Both are devoted to occupations calling for arte (technical skill) and ingegno (intelligence, talent) that fall under the sway of Mercury. In the background of the engraving, we see the crenellated façade of Florence’s Palazzo della Signoria. The street is filled with activity. A painter works on a scaffold to decorate a wall as an assistant prepares his materials. Below them an open shutter reveals the front of a sculptor’s workshop, where shop boys practice drawing. Outside, a sculptor works on a bust of a woman. In the manuscript illustration, nearly identical studios house a painter at work on a triptych and a sculptor chiseling a figure, along with goldsmiths, armorers, and an illuminator. Both illustrations also depict makers of clocks and organs, other workers who were counted among the “children of Mercury.” The similarity of their physical circumstances suggests that the status of those we would today classify as artists was not different from those we would call artisans.

Michelangelo suggested that his talent for marble carving was something he drank in as an infant with the milk of the stonecutter’s wife who was his wet nurse, and some regions did develop strong local traditions based on the proximity of natural resources. The small quarry town of Settignano near Florence, for example, produced three major sculptors of the fifteenth century (Desiderio da Settignano and Antonio and Bernardo Rossellino) and one of the sixteenth (Bartolomeo Ammannati). Lombardy, another area known for high-quality stone, produced a similarly large number of sculptors and architects relative to its population, including Pietro Lombardo and his sons Antonio and Tullio, all leading artists in Venice.

Yet it often served the most innovative talents to be outsiders, either socially or geographically. Cities with strong artistic traditions were not always the most fertile ground for change and new ideas. Training within a community or family of established masters tended to produce artists who worked in the same media and manner as the masters. Masaccio, Brunelleschi, and Leonardo—three of a handful of innovators who can be said to have first forged and later perfected Renaissance style—were sons of notaries, not of artists or artisans. Giotto, as we have seen, was a shepherd, and Michelangelo, the son of a city administrator with patrician connections. Titian, the greatest painter of the Venetian Renaissance, was not a native of Venice (although he moved there at a young age). In Florence, a relatively weak guild structure (see Guilds) that allowed foreign artists to work in the city probably helped stimulate innovation there. We should also note, however, the experience of Giovanni Bellini, who first brought the High Renaissance to Venice. Bellini was born and died in the city and trained there with his brother, Gentile, in the shop of their father, Jacopo. He seems to have made a single trip outside the Veneto—close family and city ties were not always an impediment.