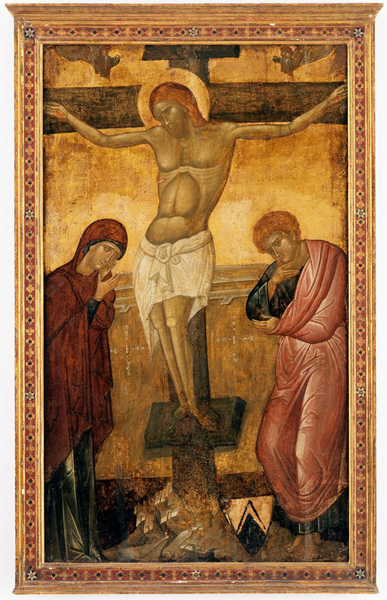

Italo-Byzantine, 14th–15th century

Crucifixion

Tempera on panel, 139.1 x 12.8 cm (54 3/4 x 32 5/8 in.)

Pomona College Museum of Art, Samuel H. Kress Collection

The transition in Italian painting from static symbols to evolving narratives was symptomatic of the more humanized conception of the Christian religion in the thirteenth century. Holy scripture was brought down to earth through the teachings of recently established Christian brotherhoods, such as those of the Franciscan and Dominican friars. Emulating Christ’s apostles, the Franciscans and Dominicans abandoned the cloistered isolation that until then had physically separated monastic orders from the secular world. Traveling and preaching widely, they disseminated new Christian narratives that characterized Jesus and the Virgin Mary in a more earthly and temporal manner. The unknown Franciscan author of The Meditations on the Life of Christ was among several thirteenth-century writers who composed imaginative “eyewitness” accounts that injected pathos and human interest into the terse biblical narrative. Elaborating on Christ’s suffering during the Passion (the sequence of incidents that preceded his crucifixion), the author suggested that these stirring narrative episodes be used as prompts to religious contemplation. He advised readers: “Turn your eyes away from His [Jesus’s] divinity for a little while and consider Him purely as a man.”2

Narrative paintings offered similar invitations for viewers to identify with the humanity of Jesus, Mary, and a panoply of saints. Carried out with increasing regard for naturalism, such paintings stimulated the viewer’s sympathetic participation in long-ago occurrences by setting the figures in motion and incorporating convincingly lifelike details unspecified by scripture. The change from static to narrative painting

Tuscan School

The Crucifixion, c. 1330–50

Tempera on wood, 62.9 x 43.2 cm (24 3/4 x 17 in.)

Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Gift of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation

becomes clear through comparison of two representations of the Crucifixion. The version by an unknown Venetian artist working in the Byzantine mode exhibits a high level of abstraction that removes the scene from earthly identification. The schematic treatment of Christ’s anatomy suggests a geometric pattern rather than a flesh-and-blood human being. Similarly, with their stiff gestures and masklike facial expressions, the Virgin Mary and Saint John the Baptist appear as abstract symbols of grief, not heartbroken mourners.

The other version of the Crucifixion, by an unknown Tuscan painter, emphasizes the physical reality and bodily suffering of Christ, whose body sags beneath its own weight. His head rolls forward, his arms appear in danger of dislocating from the shoulders, and his belly swells out from his emaciated chest. Weeping and swooning beneath the cross, the mourners react to the martyred figure and one another in a convincingly emotional manner that calls on our sympathy and establishes the image as a lifelike narrative rather than a static icon. The verisimilitude of the scene likens the divine and miraculous to our own human experience, reducing the distance between the sacred and the mundane.