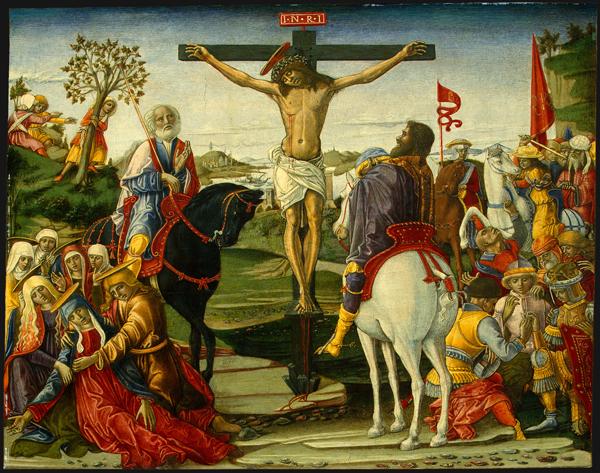

Benvenuto di Giovanni

Crucifixion, probably 1491

Tempera on panel, 42.6 x 52.8 cm (16 1/4 x 20 13/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

“And if you, oh poet, tell a story with your pen, the painter with his brush can tell it more easily, with simpler completeness, and so that it is less tedious to follow.”

—Leonardo da Vinci, “Paragone” in Trattato della pittura7

In his essay on the paragone (an argument for the superiority of painting relative to the rival claims of poetry, music, and sculpture), Leonardo da Vinci emphasized the timely manner in which painting makes an impression on the mind (see The Making of an Artist). The superiority of painting rested, in his view, on its capacity to convey instantaneously the perception of a harmonious whole, whereas poetry could do so only over time, through a sequential progression of words. “Painting presents its subject to you in one instant,” he observed, whereas poetry, through nonvisual means, impresses itself on the mind “more slowly and confusedly.”8

An instant’s glance may indeed be sufficient to form a general impression of a painting, but a full appreciation of its individual parts often requires protracted examination. This two-stage visual process was a tenet of optical theory in the fifteenth century, derived from the writings of the well-known Persian authority Alhazen (965–1039), who noted that our immediate visual perceptions are often succeeded by more attentive and contemplative scrutiny through which we build up the details necessary to form a complete mental image.

Fifteenth-century painters often structured their compositions in a manner that prolonged the second stage of visual apprehension. In this way, their paintings accommodated the same sort of sequenced meditation discussed above in relation to multiepisodic polyptychs. In The Crucifixion, probably 1491, by Benvenuto di Giovanni, the gestures and facial expressions of more than twenty figures articulate distinct dramatic vignettes that serve as emotional prompts—visual reminders of the excruciating circumstances of Jesus’s death, which worshipers contemplated at length during their devotions. Gazing at one group and then another in turn, the worshiper vicariously experienced the agonies of the scene as if events were unfolding in real time (see “Painting as an aid to religion”).

Fra Angelico and Fra Filippo Lippi

The Adoration of the Magi, c. 1440/60

Tempera on panel, diameter 137.3 cm (54 1/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

In addition to cultivating the observer’s identification with and participation in the narrative, the complex compositions and extensive casts of characters found in many fifteenth-century paintings satisfied the taste for pictorial richness and variety among artists and connoisseurs (see “Variety in an istoria”). A particularly striking example is found in another variation on the Adoration of the Magi theme (see interactive), this one by two monastic artists, the Dominican Fra Angelico discussed above and the Carmelite Fra Filippo Lippi (father of Filippino). An initial glance conveys a general impression of a semicircular arrangement of figures with a barn and ruin at the center. To visually process the colorful details of the painting and determine more exactly what is happening, we must carry out a time-consuming, piecemeal process of looking that significantly dilates viewing time. From the central foreground episode of the picture—the Adoration—our eyes soon stray to the many figures placed about the perimeter of the large circular panel (known as a tondo):

In the remote distance, at upper right, a procession of figures, some on camels, descends a hill.

- Disappearing briefly behind two centrally placed buildings, the figures reemerge at far left, streaming through an archway and proceeding toward the foreground.

- Dramatic expressions of wonderment, reverence, and curiosity dot the crowd, intermittently arresting our attention.

Other eye-catching incidents occur elsewhere in the painting:

- Stable boys attend to horses.

- Women cluster to chat in a doorway; nearby, children cling to their mother’s skirt.

- A group of seminude men clamber over a ruined wall to seek a better vantage point.

- A dog in the foreground rests.

- Farther back, a cow does the same, near a donkey with its head lowered to eat.

- A peacock and a pair of pheasants perch on a roof.

The sheer number of narrative vignettes and ornamental details overwhelms our visual sense. The complexity of the composition seems calculated to defy rapid assimilation, as if to ensure that viewing time begins to approximate the unfolding of events in real time.

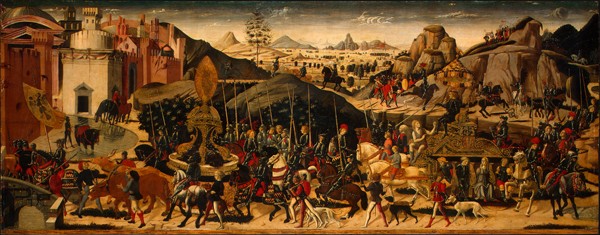

Painted for display in the bedroom or antechamber of a grand private house, or palazzo, the tondo served not only as a devotional object but also as an attractive element of decor, a precious luxury item conveying status. The imagery was constructed in a manner calculated to prompt and sustain attentive viewing. Painters devised equally complex compositions for the secular subjects that ornamented domestic architecture and furnishings. In the crowded battle and processional scenes depicted on the long panels of bridal dower chests (cassoni) and inset wall ornaments (spalliere), painters embellished the basic circumstances of the narrative with invented incidents and details that, again, draw out the viewing process. Competing vignettes and crowds of figures actually reduce narrative clarity and impede interpretation in many of these objects. Lived with and scrutinized on a daily basis, however, they may have been used primarily as domestic conversation pieces, subjects of perennial examination and debate.

Apollonio di Giovanni and workshop

Journey of the Queen of Sheba, c. 1464–5

Tempera on panel, 43.2 x 176.2 cm (17 x 69 3/8 in.)

Birmingham Museum of Art, Gift of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation

Paolo Uccello

Episodes from the Aeneid, c. 1470

Egg tempera, oil, and gold on wood panel, 41 x 156.2 cm (16 1/8 x 61 1/2 in.)

Seattle Art Museum, Gift of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation

Biagio d’Antonio and workshop

The Triumph of Camillus, c. 1470/75

Tempera on panel, 60 x 154.3 cm (23 5/8 x 60 3/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

Morelli-Nerli cassone

Biagio di Antonio, Jacopo del Sallaio, and Zanobi di Domenico

Morelli-Nerli cassone, 1472

Tempera on wood with gilding, 212 x 193 x 76 cm (83 1/2 x 76 x 29 9/10 in.)

Courtauld Gallery, London

© The Samuel Courtauld Trust/The Bridgeman Art Library

This is a painted cassone made for the wedding of Lorenzo di Morelli to Donna Viaggia di Nerli, depicting Camillus confronting the Schoolmaster of Falerii (front panel), Prudence and Temperance (at the two ends) and the Ordeal of Mucius Scaevola (spalliera) with the Morelli arms (right corner) and Nerli arms (left corner).