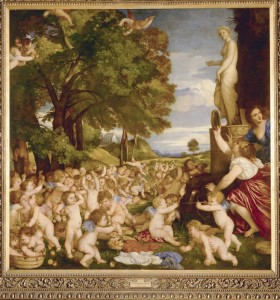

Giovanni Bellini and Titian

The Feast of the Gods, 1514/29

Oil on canvas, 170.2 x 188 cm (67 x 74 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Widener Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

“I shall have contributed only the body (corpo) and Your Excellency shall have contributed the soul (anima), which is the most worthy part that there is in a painting.”

—Letter from Titian to Alfonso d’Este, Duke of Ferrara10

Alfonso I d’Este

![Niccolò Fiorentino<br /><i>Alfonso I d'Este (1476–1534), 3rd Duke of Ferrara, Modena and Reggio (1505)</i> [obverse], 1492<br />Bronze, diameter 7.1 cm (2 13/16 in.)<br />National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection<br />Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art](http://italianrenaissanceresources.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/RP_1081-1.jpg)

Niccolò Fiorentino

Alfonso I d’Este (1476–1534), 3rd Duke of Ferrara, Modena and Reggio (1505) [obverse], 1492

Bronze, diameter 7.1 cm (2 13/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

Dosso Dossi

Aeneas and Achates on the Libyan Coast, c. 1520

Oil on canvas, 58.7 x 87.6 cm (23 1/8 x 34 1/2 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

Titian was the consummate court artist, a painter to emperors and popes. Perhaps the letter to his patron, Alfonso d’Este, was meant simply to flatter, but his words also suggest a patron’s powerful role. Alfonso commissioned The Feast of the Gods from Giovanni Bellini, who signed and dated it in 1514. It depicts a story told by Roman poet Ovid. To modern sensibilities it is unthinkable that Bellini’s work would be painted over, but that is what Alfonso ordered, twice. Ultimately it was Titian who brought the painting to its current state. In a real sense, though, Alfonso, as we shall see, must also be counted among its artists.

Giovanni Bellini and Titian

The Feast of the Gods (detail of Bellini’s tree trunks), 1514/29

Oil on canvas

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Widener Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

It was made for Alfonso’s studiolo in Ferrara. The duke originally conceived an entire suite of bacchanals, and, as his sister Isabella had earlier, he wanted them painted by the finest artists of the day. He contacted Bellini, Raphael, and Michelangelo, all around the same time. Raphael submitted a drawing, but neither his nor Michelangelo’s commissions ever materialized. The Feast of the Gods was the first painting completed for Alfonso’s study and the last major work by Bellini, who was almost ninety years old when he finished it. When Bellini died two years later, Alfonso turned to Titian and to his own court artist, Dosso Dossi, to complete the studiolo decoration. Dosso painted one large bacchanal (now lost) and a series of landscape scenes from the Aeneid. Titian contributed three paintings. An inventory made when the study was dismantled in 1598 described another work as “a painting by Bellini with a landscape by Titian.” This was The Feast of the Gods. Two distinct styles can be seen in this painting. On the right, a screen of tree trunks is thinly painted with the same detailed precision that is found in the figures. This is Bellini’s meticulous style. On the left, wild mountain terrain, animated with tiny satyrs and running stags, is brushed in Titian’s freer manner.

Giovanni Bellini and Titian

The Feast of the Gods (detail of Titian’s satyrs and stags), 1514/29

Oil on canvas

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Widener Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

Art historians concluded long ago that Alfonso had asked Titian to “touch up” The Feast of the Gods, presumably to harmonize it with Titian’s own bacchanals. X-ray and infrared studies reveal, however, that Titian had not been the first to alter the canvas. Bellini’s once-continuous screen of trees had already been replaced on the left by a low hill set with classical buildings. This change was probably made by Dosso to satisfy the duke’s taste for antiquity. Dosso also added bright green foliage to Bellini’s trees on the right. Of all

Giovanni Bellini and Titian

The Feast of the Gods (detail of pheasant), 1514/29

Oil on canvas

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Widener Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

Dosso’s contributions, it is only this foliage and the pheasant sitting somewhat awkwardly in its midst that were left unaltered. Why did Titian leave such an eccentric detail? It may be that Alfonso had painted the bird himself. He was an amateur painter and even decorated maiolica. It is also possible that bird was simply a quirky reference to himself. The duke was teased about his liking for pheasant in a play performed for him in Ferrara.

Some scholars have proposed that The Feast of the Gods, though painted years later, contains cryptic references to the duke’s marriage to Lucrezia Borgia, which took place in December 1502. The kingfisher in the foreground, for example, suggests the halcyon days  of calm that occur around the winter solstice. On the left side of the painting, Bacchus is presented as a young boy. He is in his winter guise, like the earth before the growth brought by spring and summer. The story behind The Feast of the Gods is also connected to the solstice. Ovid used it to explain the sacrifice of a donkey slaughtered each winter to commemorate the braying signal that had warned the nymph Lotis, seen sleeping at right, of the lustful approach of Priapus.

of calm that occur around the winter solstice. On the left side of the painting, Bacchus is presented as a young boy. He is in his winter guise, like the earth before the growth brought by spring and summer. The story behind The Feast of the Gods is also connected to the solstice. Ovid used it to explain the sacrifice of a donkey slaughtered each winter to commemorate the braying signal that had warned the nymph Lotis, seen sleeping at right, of the lustful approach of Priapus.

Giovanni Bellini and Titian

The Feast of the Gods (detail of Lotis and Priapus), 1514/29

Oil on canvas

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Widener Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

The members of the sophisticated court in Ferrara, and Alfonso in particular, must have delighted in all these ciphers. (Alfonso, who as a youth was upbraided by his father for having paraded through the city streets without clothes, surely would have enjoyed the tale’s risqué flavor.) Who devised the elaborate and complicated imagery? Ovid’s account, which occurs in the Fasti, would not have been widely known outside scholarly circles. It is unlikely that Bellini would have had detailed (if any) direct knowledge of it. As was true of Isabella’s suite of mythological and allegorical paintings, Alfonso’s narrative program was devised with the assistance of a humanist scholar. It was Mario Equicola, who was then in the employ of his sister in Mantua. Equicola detailed the narrative depicted in The Feast of the Gods and the other bacchanals, turning them into a thematically coordinated program. Although none survives for The Feast of the Gods, we know from correspondence about Titian’s bacchanals that the written instructions communicated to the artist were sometimes accompanied by small sketches. The task apparently took some time, and Equicola had to explain his longer than expected stay in Ferrara to Isabella, writing on October 9, 1511: “It pleases the Signor Duke [Alfonso] that I should remain here [in Ferrara] eight more days; the reason has to do with the painting of a room for which six fabule or istorie shall be placed. I have already found them and presented them in writing.”11