The small hill town of Urbino was a natural fortress, a fitting home for Federigo da Montefeltro, perhaps the most able military strategist of the Renaissance. At the time of Federigo’s death, the duke of Milan had him under contract as a condottiere for the enormous sum of 165,000 ducats. The great warrior, however, used influence and income derived from armed conflict to transform his city into a center of humanist learning and culture. The buildings and public spaces he gave Urbino exemplify the clarity and proportion of ancient architecture as reinvented by the Renaissance. Humanist Paolo Cortese, writing in 1510, named Federigo and Cosimo de’ Medici the two great artistic patrons of his day.

Federigo da Montefeltro

![Clemente da Urbino<br /><i>Federigo da Montefeltro, (1422–82), Count of Urbino (1444), and Duke (1474)</i> [obverse]; <i>Eagle with Spread Wings Supporting Devices</i> [reverse], 1468<br />Bronze, diameter 9.4 cm (3 11/16 in.)<br />National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection<br />Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art](http://italianrenaissanceresources.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/RP_1131-1.jpg)

Clemente da Urbino

Federigo da Montefeltro, (1422–82), Count of Urbino (1444), and Duke (1474) [obverse]; Eagle with Spread Wings Supporting Devices [reverse], 1468

Bronze, diameter 9.4 cm (3 11/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

The Ideal City

Attributed to Fra Carnavale

The Ideal City, c. 1480–84

Oil and tempera on panel, 80.3 x 220 cm (31 5/8 x 86 5/8 in.)

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

Among Federigo’s commissions may have been three famous views of an ideal city (in addition to this one in Baltimore, one is still in Urbino, the other in Berlin). They were meant to be set in wall panels at shoulder level or a bit above, producing the effect of looking out a window onto perfectly proportioned civic squares. They are masterful studies of perspective, with an almost airless clarity. None of the views is of a real place, although they include echoes of actual Renaissance and Roman buildings, such as the Colosseum seen here.

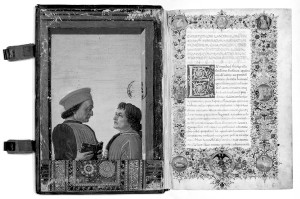

Illumination from Cristoforo Landino, Camaldoese Disputations (in Latin), 15th century

Parchment, 27 x 18.6 cm

Vatican Library, Varican State, Urb. lat. 508, cover, verso and fol. 1, recto

The library Federigo amassed was one of the most impressive in all of fifteenth-century Italy. His household staff included four teachers of grammar, logic, and philosophy; five people whose task it was to read aloud during meals; and four manuscript transcribers who worked in the palace library. The marquis built two studies (studioli) where he could enjoy humanist pursuits, one in the palace at Urbino, the other in the nearby town of Gubbio (see A Room of One’s Own: The Studiolo). Rather than have himself portrayed in a grand equestrian monument like other condottieri, Federigo was depicted as both a man of action and a man of letters.

Studiolo from the Ducal Palace in Gubbio

Designed by Federigo da Montefeltro, executed in the workshop of Giuliano da Maiano

Studiolo from the Ducal Palace in Gubbio, c. 1478–82

Walnut, beech, rosewood, oak, and fruitwoods in walnut base, 485 x 518 x 384 cm (190 15/16 x 203 15/16 x 151 3/16 in.)

Installed at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

Federigo’s studiolo from Gubbio has been reconstructed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Its elaborate intarsia was perhaps designed by Botticelli and Francesco di Giorgio; the latter was not only a painter and sculptor but also an architect employed by the marquis as a fortifications engineer. Trompe l’oeil cabinets and shelves are “piled” with objects representing different facets of Federigo’s interests and accomplishments. Arms and trophies allude to his prowess as a condottiere, celestial globes and other instruments to his pursuit of mathematics and astronomy. Musical instruments and books attest to his interest in the liberal arts.

![Adriano Fiorentino<br /> <i>Elisabetta Gonzaga (died 1526), Duchess of Urbino, Wife of Guidobaldo I </i>[obverse], probably after 1502<br /> Bronze, diameter 8.49 cm (3 5/16 in.)<br /> National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection<br /> Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art](http://italianrenaissanceresources.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/RP_1101-1-292x300.jpg)

Adriano Fiorentino

Elisabetta Gonzaga (died 1526), Duchess of Urbino, Wife of Guidobaldo I [obverse], probably after 1502

Bronze, diameter 8.49 cm (3 5/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art