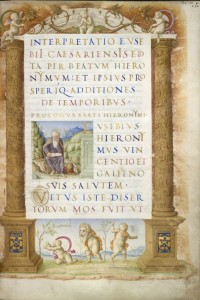

Copied by Bartolomeo Sanvito

Page from a manuscript of Eusebius’ Chronica, fol. 2r, c. 1485–8

Parchment

The British Library, London

© The British Library Board

The emphasis on learning that was at the heart of the Renaissance meant that a high valuation was placed on the book. Ancient texts, prized as fonts of knowledge, were dispersed through decorated, luxurious manuscripts prepared for patrons who appreciated the importance of the contents and the beauty of the presentation. Ownership of the classics of ancient history, poetry, and philosophy that provided models of heroic action, moral behavior, and literary style was considered an earmark of the cultivated individual. A particularly fine example of a lavish manuscript is a copy of the world chronicle that Eusebius wrote in Greek in the early fourth century; at the end of that century, Saint Jerome translated Eusebius’s text into Latin and added a prologue. Centuries later, the Renaissance scribe Bartolomeo Sanvito of Padua prepared a superb edition of Saint Jerome’s text for the important Venetian collector Bernardo Bembo (1433–1519); the volume is now in the British Library in London. The opening page of Sanvito’s manuscript includes the title of the text, in letters based on ancient Roman capitals, written in gold and colors. Placed prominently on the page is a depiction of Jerome in a landscape. He is shown in scholarly guise, intent on the open book in his lap. The beginning lines of the text are presented as if written on a fictive sheet of parchment, which is shown suspended from the triumphal arch that frames the page. Supporting the arch are two gold columns, around which wrap bands of military scenes evoking Trajan’s Column in Rome. Groups of capering infants known as putti (from the Latin word for small boys) decorate the top and bottom of the page. Bembo’s proud possession of the manuscript is made clear by his coats of arms, placed in the pedestals of the flanking columns.

Men and women associated themselves with books through portraiture that showed them in the act of reading, prominently holding books, or otherwise showing their respect and appreciation of learning. In 1555–60 Bronzino painted the Florentine poetess Laura Battiferri ostentatiously displaying a manuscript copy of the sonnets of the fourteenth-century poet and intellectual Francesco Petrarch, thereby establishing a connection between her work and that of her Florentine forerunner. The Florentine cleric Monsignor Giovanni della Casa, a member of the society of Florentine intellectuals known as the Florentine Academy and a well-known author in his own right, was painted by Pontormo around 1541/44 with an open book, marking his place with his index finger as if interrupted in the act of reading. A woman in a painting by Federico Barocci from about 1600 cradles what may be a book of devotions in her hand, but on the table at her side is another volume, this one displaying the limp vellum binding favored for humanist texts. A more modest presentation, from about 1540 by Jacopo Bassano, shows the sitter in a pensive attitude, his hands on an open manuscript on the table in front of him. The writing on the book is not sufficiently legible to identify the text, but the respectful way in which the sitter presents it for the viewer’s inspection indicates its importance to him. In an earlier manuscript from around 1500, the noted Venetian doctor and humanist Girolamo Donato, a scholar of Greek and Latin, had himself depicted on a medal with an allegory on the reverse that refers to the recovery of the antique texts. A sleeping male nude, representing antique learning, is shown leaning against an urn from which sprouts the laurel of poetic fame; two winged putti carefully and stealthily remove a set of books from his side. The putti have metaphorically “robbed” the books of antique learning from the past so that they may be used in the present. The inscription, in Greek (one of Donato’s favored languages) can be translated as “Sacred Theft”—that is, a theft that is worthy because it is in the cause of scholarship. The conceit on Donato’s medal was a popular one, copied in numerous versions, as on a small plaque in the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Jacopo Bassano

Portrait of a Man of Letters, c. 1540

Oil on canvas, 76.2 x 65.4 cm (30 x 25 7/10 in.)

Brooks Memorial Art Gallery, Memphis, Gift of the Samuel H. Kress Collection

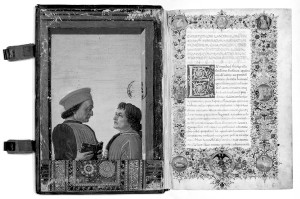

Statesmen, men of action, and rulers would often have themselves depicted with scholars and intellectuals. Federigo da Montefeltro, warrior and ruler of the duchy of Urbino, was honored by his contemporaries for his erudition and the fine library he had amassed (see “Vespasiano da Bisticci praises the library of Federigo da Montefeltro”). In a double portrait, he is shown with his favorite scholar, Cristoforo Landino of Florence. The double portrait is pasted into the front cover of Federigo’s manuscript copy of the Disputationes Camaldulenses (Camaldolese Disputations)—Landino’s treatise dealing with the active and contemplative modes of life, which he dedicated to Federigo and presented to him in a specially prepared, decorated copy. Painted in vibrant tempera colors, the double portrait presents the author and patron enclosed in a perspectival window frame set against an expansive backdrop of sky. A handsome oriental rug, which intensifies the celebratory tone of the image, is thrown over the front of the window frame. Patron and author appear, in effect, as a team, gazing intently at each other in attitudes of mutual respect.

Andrea Briosco Riccio

An Allegorical Scene, date unknown

Bronze, diameter 632.5 cm (249 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

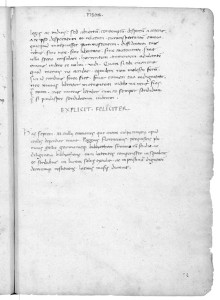

At an early stage in the new learning, scholars became interested in the reform of handwriting. Already in the fourteenth century, Petrarch had worked on simplifying the Gothic hand to make it more readable and elegant. But it was in the early years of the fifteenth century that scholars and epigraphers systematically set about developing a form of handwriting based on antique models, or litterae antiquae, as they were referred to in contemporary sources. The earliest examples can be traced to the last years of the fourteenth century and the opening years of the fifteenth. Scholars have credited the Florentine humanist Poggio Bracciolini as the pioneering figure in this reform. Antique handwriting, exhibiting clarity and restraint, was emulated especially in the copying—and eventually the printing—of the ancient texts. In a copy of Cicero’s Orations, Poggio included a note at the end of the manuscript explicitly acknowledging the importance of the rediscovery of ancient texts and his role in their renewal: “Formerly lost owing to the fault of the times, Poggio restored to the Latin-speaking world and brought it [i.e., Cicero’s Orations] back to Italy, having found it hidden in Gaul, in the woods of Langres and having written it in memory of Tully [i.e., Cicero] and for the use of the learned.”

Illumination from Cristoforo Landino, Camaldoese Disputations (in Latin), 15th century

Parchment, 27 x 18.6 cm

Vatican Library, Varican State, Urb. lat. 508, cover, verso and fol. 1, recto

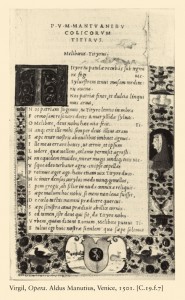

Assisting dissemination of the new learning was the rise and proliferation of printing presses. Venice, which attracted German printers in the middle years of the fifteenth century, was a locus for the new printing industry. It was, however, the press of the Roman printer Aldus Manutius, who arrived in Venice at the end of the fifteenth century, that became associated directly and extensively with the new learning. One of the major endeavors of the Aldine press was the printing of small, easy-to-handle volumes of Greek and Latin classics. Aldus has been called the inventor of the “pocket book.” Printed in a carefully cut typeface that closely approximated the handwriting of the humanists—the typeface we now call “italic”—and intended for connoisseurs as well as for intellectuals with limited time at their disposal, the volumes were an instant success. In the preface to a volume of Horace, one of the early productions in the new format, Aldus addressed himself to the Venetian statesman Marino Sanudo, recommending his volumes of the classics for their readability during moments free from other obligations: “The small size of their dimensions invites you to the reading of them in the moments of repose from your public duties or from the writing of your history of Venice.”5

Page from Cicero’s Oration, 1417

Paper, 21.6 x 15.2 cm (8 1/2 in. x 6 in.)

Vatican Library, Vatican State, Vat. lat. 11458, fol. 94 recto

The typeface was so novel and revolutionary that Aldus applied to the Venetian government for a special copyright privilege to cover his exclusive use of it (see “Privilege is granted to Aldus Manutius by the Venetian government for the production of his new italic typeface”). When other printers, such as those of Lyon, attempted to sell pirated editions that had the look of the Aldine volumes, Aldus sued to protect his invention.

Page from Virgil, Opera

Printed by Aldus Manutius, Venice, April 1501

Printed typeset

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Rés. p. Yc. 1265

The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY

Among the first volumes to come off the press were the time-honored texts of classical as well as prehumanist and contemporary authors, including Virgil, Petrarch, Dante, and Pietro Bembo. Aldus also printed, in 1499, a novel that illustrates some of the curious byways the new learning would take. The book was the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, a Greek title that roughly translates as The Struggles of Poliphilus in a Dream (Poliphilus being the name of the hero of the story). Written in a language that is part Latin, part Greek, and part Italian, and profusely illustrated with woodcuts, the volume may have been intended to celebrate the erudition of the author, a certain Fra Colonna, whose identity has never been satisfactorily established.

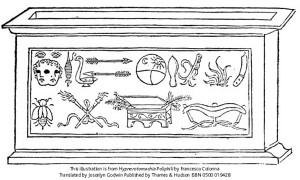

Francesco Colonna

Sarcophagus with hieroglyph

Illustration from the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili

Published by Aldine Press, Venice, 1499

Thames and Hudson, Ltd.

The book takes the form of the romantic journey of Poliphilus in search of his true love, Polia. The quest takes him through a marvelous and varied antique landscape filled with architecture, sculpture, and artifacts from the past, large numbers of which are reproduced in the illustrations that form an important part of the presentation. One of the particularly interesting aspects of the book is Poliphilus’s “discovery” of works of art that bear cryptic symbols, a number of which have been shown to have been taken from known antique monuments. With great joy, Poliphilus comes upon “noble fragments” carved with symbolic images. He describes the depth of his reaction: “Rejoicing with incredible happiness at such a variety of antiquities and magnificent works, my soul again felt the insatiable desire to wander on and investigate fresh novelties.”6 The language of symbols on pieces illustrated in the text, the majority of which can be deciphered today based on contemporary Renaissance sources, belongs to the Renaissance effort to understand the sometimes mysterious world presented by the antique past. An illustration bearing the motif of the dolphin curled around the shaft of an anchor—the dolphin indicating speed, the anchor indicating stability and firmness—transmits the message of festina lente (make haste slowly), a popular Renaissance conceit carrying the idea of the readiness to move forward but with prudence.